FRED Dibnah was undoubtedly an ordinary man who made himself extraordinary.

He was born in Bolton on April 28, 1938, and as a child was fascinated by the huge steam engines used to power the textile mills that helped place the town at the forefront of the enduring Industrial Revolution that transformed the landscape.

From his bedroom window, he could see steam locomotives at work, but his attention was especially caught by the steeplejacks scurrying around the many tall buildings near his home. When he watched his first giant chimney being felled, he was hooked.

Unusually artistic, young Fred attended the local art college where his own work was often on an industrial theme. He found work as a joiner, but he hung around the steeplejacks, learning their trade. He was helped by a draughtsman who taught him how to erect ladders up a 200-foot chimney stack and installed lifelong engineering principles.

Soon, he was asked to perform tasks like pointing a gable end and his skills swiftly moved him into the practical, rarified world of men who worked in the sky. Fred became a fully fledged steeplejack and a familiar sight around the town.

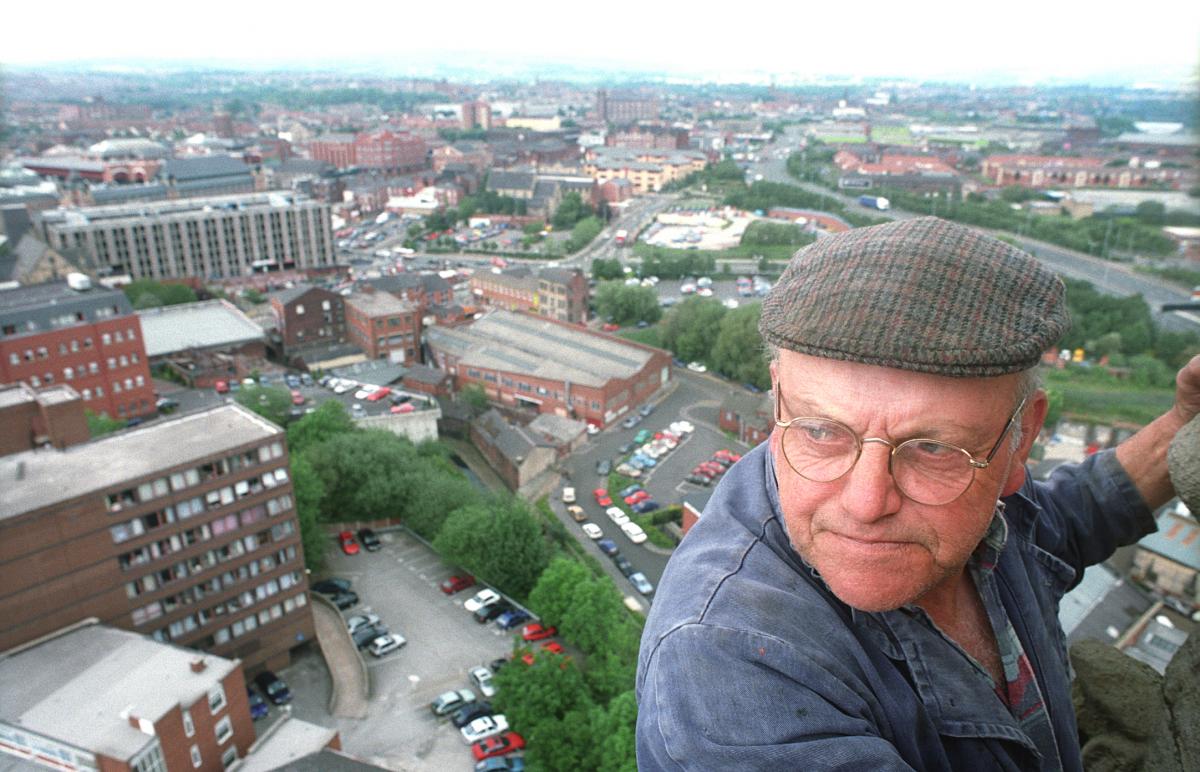

He was filmed by the BBC as he worked on the clock tower in Bolton’s Victoria Square. TV producer Don Howarth saw the footage and was intrigued by the passionate little man with the unusual skills.

His programme “Fred Dibnah: Steeplejack” introduced Fred - a modest man who never quite believed that people found him interesting - to a viewing nation that ultimately never grew tired of him.

His TV career turned him into a celebrity and his love of the nation’s architecture and its industrial legacy meant he hosted a stream of programmes still being screened today.

They brought him fans not only from all around the UK but from all over the world. Announce you’re from Bolton in Spain, Singapore or San Remo and someone will immediately connect you with Fred Dibnah.

He was very much a what-you-see-is-what-you-get person. In his workwear he would pass unnoticed in the street. Dressed up, he wore a suit with a waistcoat, a gold watch chain draped across his tummy, often all teamed with his big boots and flat cap.

But he could talk for hours with impressive knowledge and energy about steam engines, beautiful lofty buildings – ironically, many of which he had been called on to demolish – and the glorious British past. Fred was a man born out of his time, but we were glad of it.

The last time we spoke he was already ill. The weather was chilly but we stood in the garden of his historic home in The Haulgh, surrounded by his crammed workshop and the replica mineshaft he had created with his devoted friends.

Fred clutched a mug of tea and chatted almost non-stop for two hours about how he wanted his house and garden to be a working memorial for the future. He showed me beautifully drawn plans he had created. “Take them home, love – have a good look,” he instructed me. “I won’t be here but this place will.”

He died later that year and, indeed, his home is now the heritage centre he wanted. His memory remains intact thanks, not just to this or even to the enthusiasts who have helped keep his dreams and his passions alive but to a town that was proud of a talented son. One that recognised that ordinariness can become greatness, even in a flat cap.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel