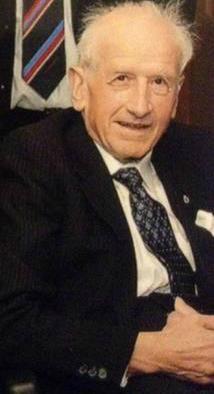

FOR someone with such a fearsome reputation on the pitch, Roy Hartle was every inch the distinguished gentleman off it.

Immaculately groomed and carrying that distinctive silver-topped walking stick, had you bumped into the legendary full-back as he walked round the hospitality suites at his beloved Wanderers in days of better health, it was impossible to think this was a man who had opposition wingers cowering in fear for the whole of his one-club playing career.

Hartle made an instant impression on Wanderers chairman Phil Gartside.

“I vividly remember the first time I saw Roy play,” he wrote in the foreword to the excellent biography, “Legend: The life of Roy “Chopper” Hartle, by John Gradwell. “I was 11 years old and it was an FA Cup third round match at Burnden Park against Bath City.

“From the start, I could not believe how tough this guy was. It looked as if a runaway train wouldn’t stop him and I almost, but not quite, felt sorry for the wingers whose duty it was to try and get round Roy and stay in one piece.

“But Roy wasn’t just a football hard man. He was a leader on the pitch who went on to become an inspirational captain of the club. “ That classy demeanour and clipped West Midlands accent no doubt swayed the opinion of the odd referee, considering he picked up just one booking in 499 appearances for Bolton, albeit in a very different footballing age.

But for every account from an opponent who had been unwillingly introduced to the gravel track which ran parallel to the touchline at Burnden Park, there was one extolling Hartle’s virtue as a player and a person.

Hartle will always be synonymous with Bolton’s other no-nonsense full-back, Tommy Banks, who he met whilst doing National Service at Oswestry.

Unlike Banks, Hartle did not win international recognition from England – with Birmingham’s Jeff Hall and later Blackpool legend Jimmy Armfield proving difficult customers to overcome.

Hartle’s career was not without its disappointments, dropped to 12th man for the 1953 FA Cup final without explanation despite having played in all the other rounds, he was also denied a chance to make a 500th appearance when he was released by Bolton in 1966.

Indeed, he lost touch with the club until Nat Lofthouse brokered a reconciliation in the late eighties, which would see him team up again to provide hospitality at Burnden and later the Reebok.

In 2004, Wanderers renamed the Emerson Suite in Hartle’s honour and three years later he would walk out, bursting with pride, to represent the club at the opening of the new Wembley Stadium.

Hartle could often prove a big attraction away from home too – as the club found out on its first visit to Arsenal’s Emirates Stadium.

“We had laid on travel and Roy travelled on one of the coaches,” recalled Andrew Dean, the club’s promotions manager. “After the game had finished we all got back aboard but he was nowhere to be seen. We had a police escort at the ready, everyone was frantic we were pulling our hair out wondering ‘where was he?’ “All of a sudden, walking up the road was Roy with his stick in hand, casual as you like. He got back on the coach, sat down and in that crisp accent of his said, ‘okay, we’re ready to go.’ “We asked him where he’d been and he answered as matter-a-factly as you like ‘I’ve just had a drink with Arsene Wenger.’”

Sir Bobby Charlton was another famous name who would never leave a Bolton game without dropping in on his old friend.

Just three months on from representing Bolton at Wembley, a severe stroke robbed Hartle of much of his mobility but undeterred and supported by his wife Barbara, he battled back, continuing to attend games, even using his story to promote the excellent work of the Stroke Association.

Flags were lowered to half mast at the stadium yesterday where everyone had a tale to tell about a man who had become part of the fabric of life at Bolton Wanderers.

Hartle leaves behind a loving wife, two children, grandchildren, and just four surviving members of the last truly great Bolton Wanderers team which lifted the FA Cup in 1958.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel