AS the people of Bolton head out to clinics across the borough to have their flu jabs it’s worth remembering that it is 100 years since a strain of Spanish flu wiped out up to 228,000 people in the UK.

The outbreak which was first detected in Scotland in May 1918 was even more rapidly spread with the return of thousands of British troops from the French trenches following the close of hostilities in November, 1918.

Estimates of this spread which was deemed a global pandemic continued into 1919, but with less of a ferocity, claimed the lives of more than 50 million people worldwide.

However, as the news pages of the Bolton Evening News archive reveals, this was not the first outbreak of this type to hit Bolton, with a previous influenza outbreak in 1837 claiming the lives of 420 citizens.

One of the many victims, of the 1918 outbreak, which at its height was claiming dozens of victims each month, was Walter Bromiley, of 23, Queensgate, who had been the secretary of Bolton Philharmonic Society for the previous 25 years. He had been walking home from a Messiah rehearsal, when according to a report in the Bolton Journal and Guardian, he collapsed with severe pains. He died of pneumonia at his home two days later.

The outbreak targeted young adults between 20 and 30 years old were particularly affected and the disease struck and progressed quickly in these cases. Onset was devastatingly quick.

According to one report, those Boltonians fine and healthy at breakfast could be dead by tea-time.

Within hours of feeling the first symptoms of fatigue, fever and headache, some victims would rapidly develop pneumonia and start turning blue, signalling a shortage of oxygen. They would then struggle for air until they suffocated to death.

By the end of October 1918, and under the headline Flu At Summit, it was being reported in the Journal that schools had been shut down to try to prevent the spread of the outbreak in the hope: “the power of the epidemic might be broken”.

It comments further: “The disease so far as Bolton is concerned, is thought to be at its summit and while there are not yet any signs of its decline it is hoped that things will not be worse.”

According to the Journal report it depended who was to be believed as to the cause of the outbreak with some suggesting it was due to people not having enough fats and or there had been an excess of rain.

However, the newspaper came to a more learned conclusion by explaining: “The most reasonable thing is to assume that it is one of those periodical outbreaks where the bacillus has the aid of many contributory causes and not one in particular.

“The attack is generally a sharp two-days affair and a quick convalescence. Great care should be taken for at least 10 days after.

“The first signs, for the majority of the deaths are due to pneumonia, which has supervened on the influenza owing, as a rule to the patient going out too soon.”

By the following week, on November 1, the newspaper stated that influenza “had been rampant with hundreds of cases and 30 deaths, with schools across the borough remaining closed for the time being.

A well known song captured the utter hopelessness for many which went was a favourite with people across the country:

I had a little bird

Its name was Enza

I opened the window,

And in-flu-enza.

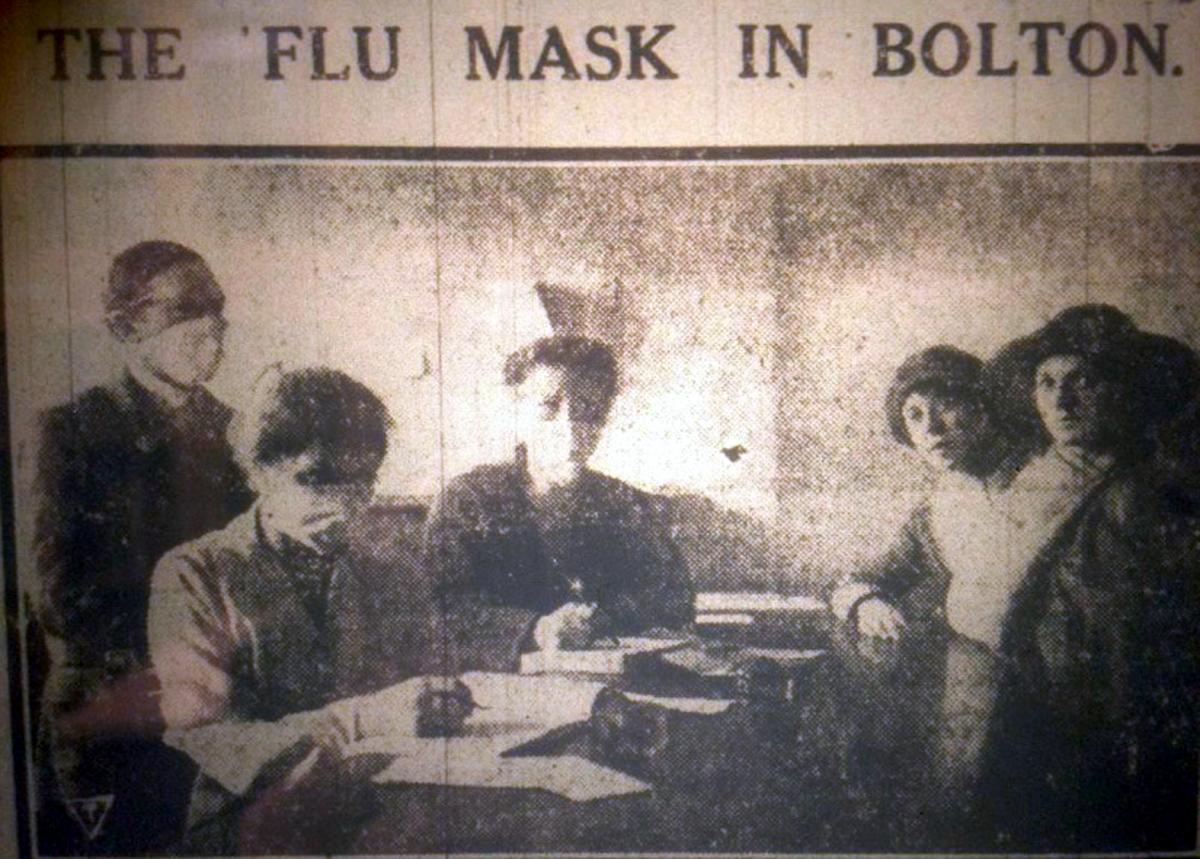

The reports on the outbreak are sparse on the outcome but by early 1919 the town’s War Pensions Committee staff were ordered to wear face masks to try to prevent them catching influenza.

The Journal report explains: “Prevention is better than cure in the cause of influenza. One Bolton gentleman(Lieutenant Farnworth) has taken the bull by the horns, or rather the germ at the nose and mouth of potential victims. His office staff was becoming so depleted as a result of the epidemic, that those who were left were issued with ‘flu masks’”

The newspaper then engages in a militaristic style of language by explaining:”Staff engaged in their daily tasks armoured, be it only with muslin against the attacks of the enemy, who had already entrenched himself in the office.”

It adds: “The Medical Officer of Health Dr Gould exhorts increased care just now whilst the disease is calculated to be at the height of its virulence.

“As to the statistical facts of the epidemic, in town, it’s pointed out that whilst Bolton’s death rate last week rose from 44 to 50 of which 21 are attributable to influenza, this was much lower than other similar towns and very much below the figures recorded in several towns up and down the country during the epidemic of last October.

“So whilst there is a reason for alarm, there is need for the exercise of all means of prevention

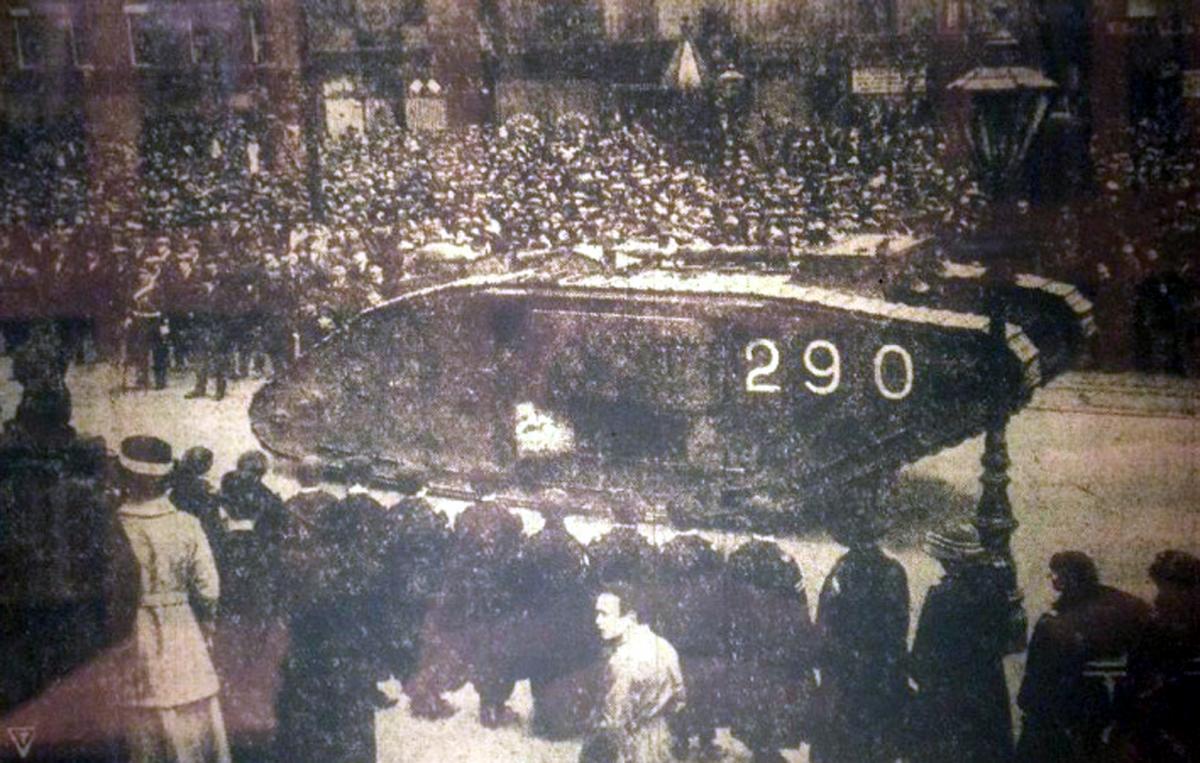

Historians suggest that the outbreak hit the UK in a series of waves, with its peak at the end of WW1. Returning from Northern France at the end of the war, the troops travelled home by train. The flu spread from the railway stations to the centre of the cities, then to the suburbs and out into the countryside.

Hospitals were overwhelmed and even medical students were drafted in to help. Doctors and nurses worked to breaking point, although there was little they could do as there were no treatments for the flu and no antibiotics to treat the pneumonia.

Nearby, the epidemic had a much greater impact with The Manchester Guardian reporting that by November 1918, all the city’s mortuaries were full, with undertakers working night and day to keep pace with burials at cemeteries.

Every effort was being made to secure the release of skilled coffin-makers from the army, and soldier labour for the digging of graves.

In a letter dated 29 September 1918, published in the British Medical Journal in 1979, Professor Roy Grist, a Glasgow physician, described the deadly impact of the infection.

“It starts with what appears to be an ordinary attack of la grippe. When brought to the hospital, [patients] very rapidly develop the most vicious type of pneumonia that has ever been seen. Two hours after admission, they have mahogany spots over the cheek bones, and a few hours later you can begin to see the cyanosis [blueness due to lack of oxygen] extending from their ears and spreading all over the face. It is only a matter of a few hours then until death comes and it is simply a struggle for air until they suffocate. It is horrible.”

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here