SUICIDAL thoughts could be affecting as many as 20 per cent of adults suggested a 2016 survey.

Charity MIND says that every two hours someone in England and Wales will take their own life.

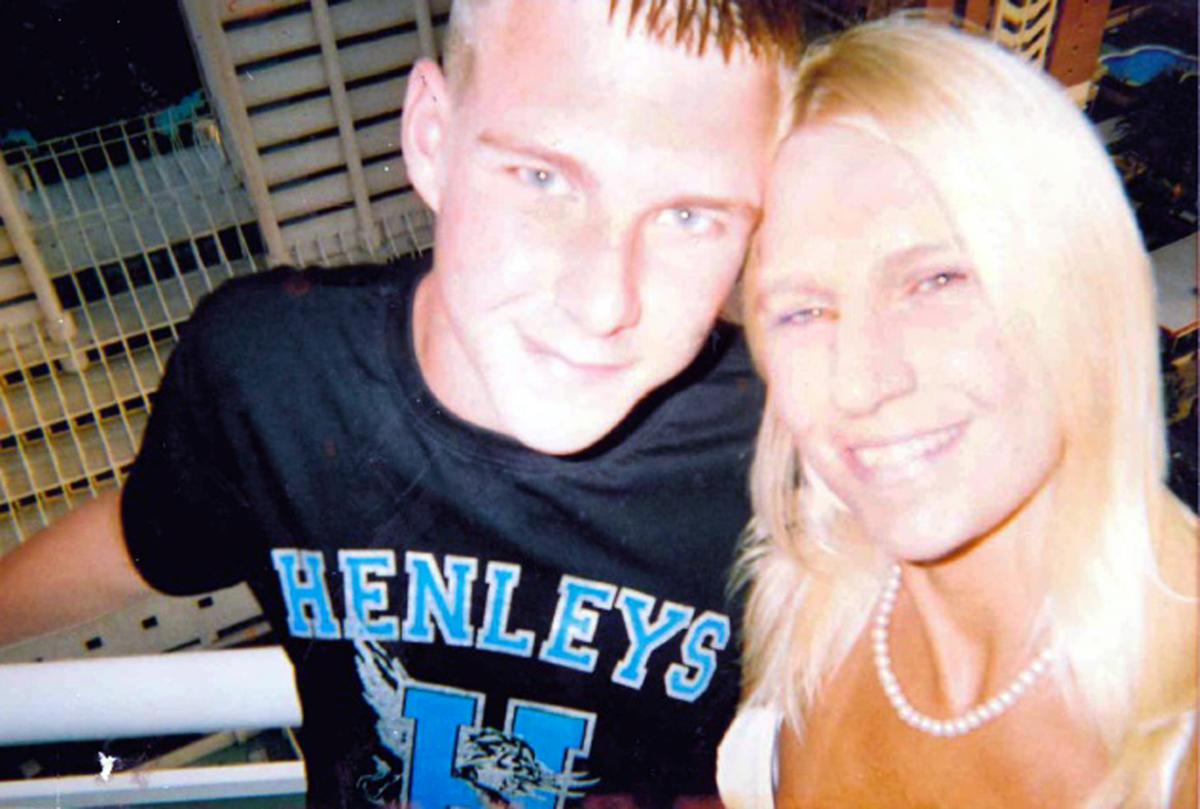

A 24-year-old from Bolton did. MARY NAYLOR reports on why his mother feels failed by the mental health services.

A MOTHER facing Christmas without her son is making a desperate appeal for suffering families to get the mental health services they need.

Alexander Banerjee suffered with anxiety and depression and found it very difficult to leave the house.

His mother Jane Alexander said he would even order groceries to the front door, despite living near the Asda in Astley Bridge.

Even when his grandparents came to visit he would become anxious and find it difficult to cope.

Alexander took his own life after he missed an appointment with a mental health worker. He was discharged from the service and two days later was found dead.

Ms Alexander from Astley Bridge says she believes that if her son had seen a mental health worker when he needed help, he would still be alive today.

She says life without her son is a daily struggle and wrote to The Bolton News to make a heartfelt appeal for mental health services to be made easily accessible for people who are suffering.

Ms Alexander says she believes that if Alex had seen a mental health worker at home, because he had felt unable to leave the house, he would still be alive today.

At an inquest into Alex’s death, she said a GP had told the family there was no at-home service for mental health patients.

But local mental health workers then told The Bolton News that such a service did exist and that a GP would have been able to refer Alexander for help from home.

The service has been in place since a month before Alexander died.

A spokesperson for Greater Manchester Mental Health NHS Foundation Trust said: “Since April 2018 every GP practice in Bolton has had access to a primary mental health practitioner, who is managed by GMMH.

“These practitioners provide a link between GP surgeries and our services in Bolton and make it much easier for people to access the care they need when they need it.”

Ms Alexander, aged 49, believes the service Alex had previously received seven miles away in Darwen was superior to that offered in Bolton.

In Darwen Alex received at-home visits every two months, but when he moved back in with his mother in Bolton four years ago, those visits stopped.

Ms Alexander, who changed her last name in her son’s memory, explained that when he lived in Darwen the at-home mental health service was on call 24 hours a day.

When Mr Banerjee took an overdose, a member of the team visited him that night.

Ms Alexander said: “All he had to do was ring his worker and he was there and it was the same person.”

In Bolton Alex was put under the care of the Rivington Unit in Minerva Road which did organise two home visits after he tried to take his own life two years ago.

He was spotted alone near Smithills Coaching House and a member of the public called the police. His mother met him in hospital. She said: “I’d never seen him in such a bad way. He had totally broken down. It’s so frightening to see your son like that.”

At that time she asked for Alex to be sectioned, but said nurses stalled until Alex came round and then begged her not to section him.

Alex was then seen twice at home by two different mental health workers. He told his mother he could not “keep going back to the beginning every time” with a new person.

Ms Alexander wants the at-home service to be improved to cater for people who find it hard to leave home and attend appointments. And she wants it to be made available before someone has tried to take their own life. She said: “I do believe he would still be alive today if they had that.”

She said: “I think a lot of teenagers are like Alex, they need the home visit — those who are on anti-depressants and keep cancelling appointments because they can’t always get there.

“If they are talking about suicide I think that warrants home visits. You need the home visits and it has to be the same person — you need to build trust.”

Ms Alexander believes her son struggled with mental illness from around the age of 14 and was shocked to learn at the inquest into his death that he had been self-medicating using diazepam — a drug used to treat anxiety, among other conditions.

Shortly before he died Ms Alexander managed to get her son to attend an assessment appointment at the Rivington Unit. She said she was “so proud of him” for managing it and he had told her “how difficult it was to go”.

In the waiting room Ms Alexander said she was “shocked” by the number of people coming and going and people suffering panic attacks, which added to Mr Banerjee’s anxiety. She said: “I found it all horrendous.”

It took three weeks for a report of his assessment to come back and Mr Banerjee was then referred for an appointment. Ms Alexander did not know about this appointment and her son missed it because he felt unable to attend.

His missed appointment was May 11. He was dismissed from the service the same day, says his mother. On May 13 Mr Banerjee took his own life.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel