AS British business sets itself up for the hardest of landings by stockpiling products ahead of a potential ‘cliff edge’ Brexit – it’s worth recounting contingency plans put in place in Bolton during the Second World War to take care of the populace.

At that time there were fears not only of invasion by Germany, the other worries centred around places including Manchester and Liverpool which were subject to heavy bombing by the Luftwaffe and that was when stockpiling and storage of vital products were moved to the less well targeted streets of Bolton.

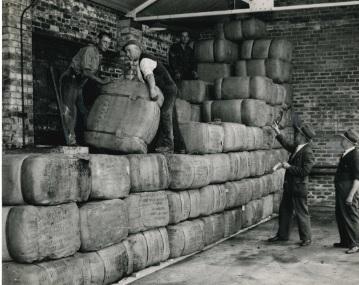

One commentator remarked: “Convoys of lorries, stacked with food, threading their way through town; bales of cotton stored in the open at places like Bradford Park; hundreds of railway wagons being unloaded at top speed.

“Those were some glimpses at Second World War-time Bolton, when the town filled a new and strange role. For Bolton was, during the war, an inland port. Its "docks" and warehouses included a theatre, mineral water works, bleachworks, a tram shed, and cotton mills.”

As workmen were loading gold ingots and precious artefacts from the country’s museums onto ships for transportation down the Manchester Ship Canal and across the Atlantic for safe keeping, Bolton was storing goods of every kind, including cotton, resin, rubber, Epsom salts and many other commodities.

The commentator observed: “I know that many of you will remember Harry Mason and Sons, Limited. That firm alone, for example, handled well over nine million "packages", ranging from cartons of food to bales of cotton having a value even then of something like £50,000,000, and a total weight of more than three quarters of a million tons.

An interview conducted with Boltonian Leila Parker in 2005 in which she recounted that her new husband Joe had worked at Mason’s in 1940.

She said: “Joe worked at Harry Mason's and if he had been a little bit older they could have kept him back, because they were storage for the Ministry of Food, but he was 24 and he had to go (to war).

It meant that Bolton became one of the big storehouses of the country through force of circumstance and the accident of its location.

As warehouse space was lost through the repeated bombings of Liverpool and Manchester, and as, owing to the shortage of shipping space, vessels had to be unloaded in a matter of hours, storage space in an area that was comparatively safe and yet was close to these ports became essential.

However, the stockpiling began in a small way when in 1939 the imminence of war led the government to build up reserves of building materials in various parts of the country, for use following air raids.

These reserves were intended primarily for "first aid" repairs, and to enable "blitzed" works to resume production as quickly as possible, and also to repair damaged houses.

This meant working out a scheme both speedy and elastic, and not tied up with red tape. The systems devised to meet these emergencies proved very successful.

However, it meant that the four members of the Mason firm, Harry, Will, Tom and Jim had to be on call by telephone 24 hours a day, seven days a week, but it also meant that emergency works officers and surveyors could call on them at any time and be supplied with materials which included tarpaulins, glass, roofing felt and windows at a few hours' notice.

There was no question of indents or authorities to be consulted before delivering, and the system worked well. During the first heavy bombing of Manchester, for instance, materials were delivered to damaged hospitals and houses the following morning, and many workshops were able to begin production again within a matter of hours.

Bolton's development as an inland port began in earnest when the Ministry of Food started its "buffer" depots, to which food could be transported from the dangerous areas of the docks and kept in comparable safety.

One of the first consignments of food to Bolton under this scheme arrived in September, 1940 and was 25,000 cases of tinned milk, weighing 600 tons, which had to be accepted at the rate of 150 tons a day. This seemed tremendous then, but as time went on, these figures were seen to be relatively small. One warehouse alone contained 4,000 tons of food at one time.

On one occasion 400 tons of lard, packed in 5lb boxes, arrived in a hurry, with the instruction that it must be unloaded, stored in the open, and sheeted up for for the night. The next day, however, turned out to be very hot, the lard began to melt, and men had to be employed to throw water on the tarpaulin to cool it!

Bolton, of course, has long been known as the home of cotton; during the war years it was in a very special sense. In 1941, it was found that the country's stocks of raw cotton had fallen to a low level, and the Government decided that imports should be increased. There was, however, nowhere to store it, so the decision was made to keep it in the open.

The first cotton depot was at Halliwell, where 12,000 bales had to be taken in at short notice, but this depot soon proved to be too small and Bradford Park was taken over for the same purpose. In the early days, in bitterly cold weather, clerks sat in cars which were used as temporary offices. Eventually there were 16 cotton storage sites in the area sheeted with tarpaulin.

All this storage required considerable organisation, with telephone calls almost a nightmare at times. During the war years, the Masons had annual telephone bills of about £1,000 (a vast amount in those days).

Masons alone had 13 depots under their control, and up to the end of 1945 they had housed at one time or another 42,215 tons of food of all kind, including flour, milk, fruit, fish, jam, biscuits, and even beer. The value of the food handled by the firm was £2,402,000.

The commentator adds: “It proves, though, that Bolton not only sent her sons and daughters to the fronts of the Second World War, but in a very real way became one of the country's subsidiary ports, and lonely night watchers on such sites as Bradford Park could rightly feel that they had done their share in maintaining Britain's lifeline.

“These supplies were called for as late as Christmas, 1944, when V1 bombs were dropped at Tottington, Worsley and other places.

“There was, at one time, 3,901 tons of arsenic in the town, enough to have poisoned the whole of the German Army if it could have been administered!”

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel