THE Bolton News can claim some great writers but even they pale into insignificance compared to some of our previous “staff”.

Thomas Hardy, Wilkie Collins, H G Wells, Arthur Conan Doyle, George Bernard Shaw, J.M. Barrie, Robert Louis Stevenson, Wilkie Collins, E. Nesbit, and Arnold Bennett all had contracts with what was then known as The Bolton Evening News.

It was back in the 1870s that the newspaper’s owner, W.F. Tillotson hit upon the idea of establishing a fiction bureau and newspaper syndicate.

Tillotson thought of the value of stories as a help to circulation, especially of the weekly journals.

He wrote letters to authors inviting them to join the syndicate. The deal was that the authors were paid for their stories by Tillotsons who then sold them on to other newspapers. It didn’t take long for Tillotsons become established agents for the supply of fiction to many parts of the world.

At first, some established writers turned up their noses when they heard of Tillotson’s idea; a provincial publisher putting their novels into cheap newspapers week by week? The cheek of the man!

But soon his enthusiasm opened the eyes of the authors to the possibilities of the scheme, making them realise that through the syndicate they could reach thousands of writers they would not otherwise reach.

Many authors who may otherwise have remained obscure climbed to fame through the syndicate.

Tillotson had the foresight to keep the correspondence with the authors and those literary treasures are still held in our archives today.

In the decades since the letters were first sent, many of the authors became famous across the world, but at the time of the correspondence they were not treated with any particular deference.

Robert Louis Stevenson, the man who wrote Treasure Island and The Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde, found himself unceremoniously dumped by Tillotsons when it withdrew an agreement.

Writing in March 1888, Stevenson said: “I am indeed troubled you should have a connection with me always so unlucky. What can I say better than better luck next time.”

And Wilkie Collins, the author credited with writing the first detective story, was keen to offer reassurance in the hope of getting his short stories published.

In a letter dated March 8, 1883, he stressed that his two stories “have both been already punctuated”.

R.D. Blackmore’s most well-known novel is the Exmoor romance, Lorna Doone.

Evidently, he had received some criticism over the length of one of his offerings because he wrote back promising to sub-mit “a work of lesser bulk”.

Not all of the aspiring authors were prepared to take things lying down and William Black, who was favourably compared to Anthony Trollope, but whose popularity and fame didn’t endure, was one of them.

In January 1897 he angrily wrote to Tillotsons: “Do you purpose printing samples of my new novel, to be hawked about newspaper offices for approval? I ask if you subject the other authors who write for you to a similar degradation?

“But the fact is that for a long time back every letter that I have received from your firm has contained some further and further demand, each one more extraordinary than its predecessor.”

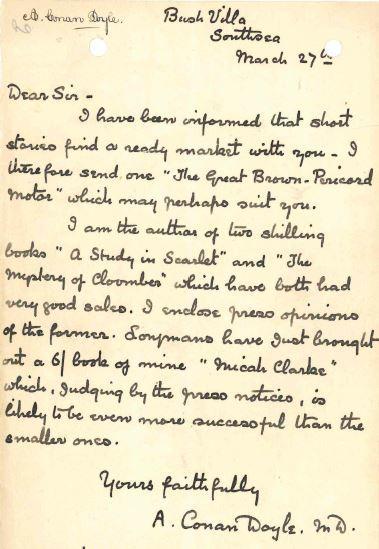

In June 1882, Sherlock Holmes author Arthur Conan Doyle tentatively wrote: “I have been informed that short stories find a ready market with you – I therefore send one, The Great Brown-Pericord Motor - which may perhaps suits you.”

He modestly mentions: “I am the author of two shilling books ‘A Study in Scarlet’ [the very first Sherlock Holmes story] and ‘The Mystery of Chambers which have both had very good sales.”

In another letter he puts in a word for his sister: “My sister has written a second story “The Secret of the Moor Cottage” which really is a rattling good tale, especially in a serial. I have advised her to send it you and I hope that it may prove to be in your line.”

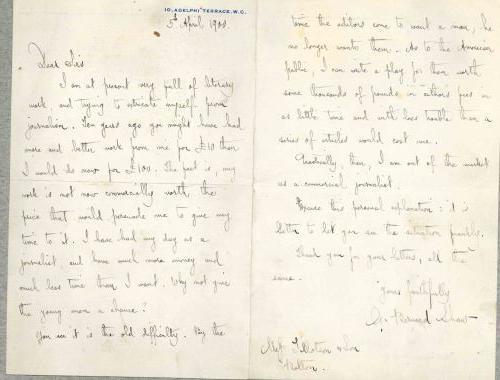

Revealing an intention to re-focus his career direction, George Bernard Shaw wrote in April 1900: “I am at present very full of literary work, and trying to extricate myself from journalism. Ten years ago you might have had more and better work from me for £10 than I would do now for £100… I have had my day as a journalist, and have much more money and much less time than I want. Why not give the young men a chance?”

Thomas Hardy not only wrote to Tillotsons offering his novel The Well Beloved, he also went into detail about its plot and style.

“The story, though it deals with some highly emotional situations, is not a tragedy in the ordinary sense….There is not a word or scene in the tale which can offend the most fastidious taste; and it is equally suited for the reading of young people and for that of persons of mature years.”

In July 1881 Hardy wrote: “I should be very happy to write you a short Christmas story for your supplement. My price would be six guineas per 1,000 words.”

He obviously had a good relationship with the paper because when Tillotson died in 1889, Hardy wrote top express his condolences saying: “I was much struck with the straightforward sincerity of his character.”

Later that year, however, the working relationship soured.

Hardy had been commissioned to write a story but it was rejected on the grounds of blasphemy and obscenity.

The book turned out to be Tess of the d’Urbervilles, one of Hardy’s greatest works.

Pushing his luck, and attempting to drive a hard bargain in January 1891 was Hall Caine, another author who, like William Black, was massively popular then but who has since fallen out of favour.

He was returning the final proof of his story, The Last Confession. Tillotsons had asked for about 14,500 words in three instalments, but due to “artistic compulsion” he submitted 23,500 words in four instalments.

In a letter dated January 12, 1891, he wrote: “I think you will agree that it is as strong a piece of work as I have ever done at all, and I trust it will please your clients. But in consideration of the great increase in matter, and of the extra instalment, is it not fair to ask you to add something to the fee that you were to send me?”

Another literary luminary who was hoping Tillotsons might boost his writing career was H.G. Wells.

The visionary author, best known for his novels The War of the Worlds, The Time Machine and The History of Mr Polly was keen to follow Tillotsons’ plans, writing: “I shall be glad to fall in with your suggestion that I should send you one 5,000 word story instead of two short ones.”

Perhaps the most intriguing letter came from the celebrated Cornish author, Sir Arthur Quiller Couch. Writing from his home in Fowey on November 23, 1893, he said: “I hope that by promptly challenging the Bishop’s libel that I have at any rate prevented the boycott which he advocated in these parts.”

Since we only have a one-sided correspondence, the meaning of his message is all the more cryptic.

Who was the bishop? What was the libel?

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel