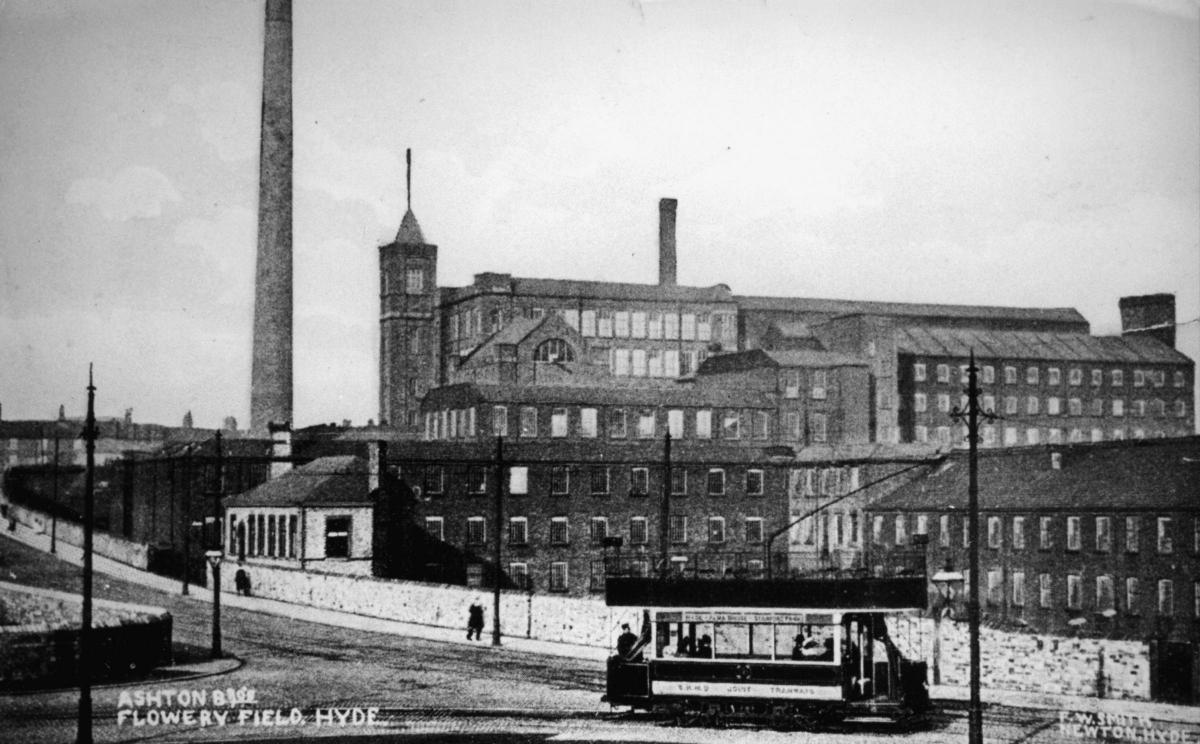

IT was a summer day which was marked with particular excitement by the workers of Carrfield Cotton Mill and one in which the looms and engines of industry sat in idle silence.

But as the men and women of Flowery Field enjoyed their annual work’s picnic outing to Blackpool the vacated mill bore witness to a barbaric rape and murder which shocked a community to its core and made legal history.

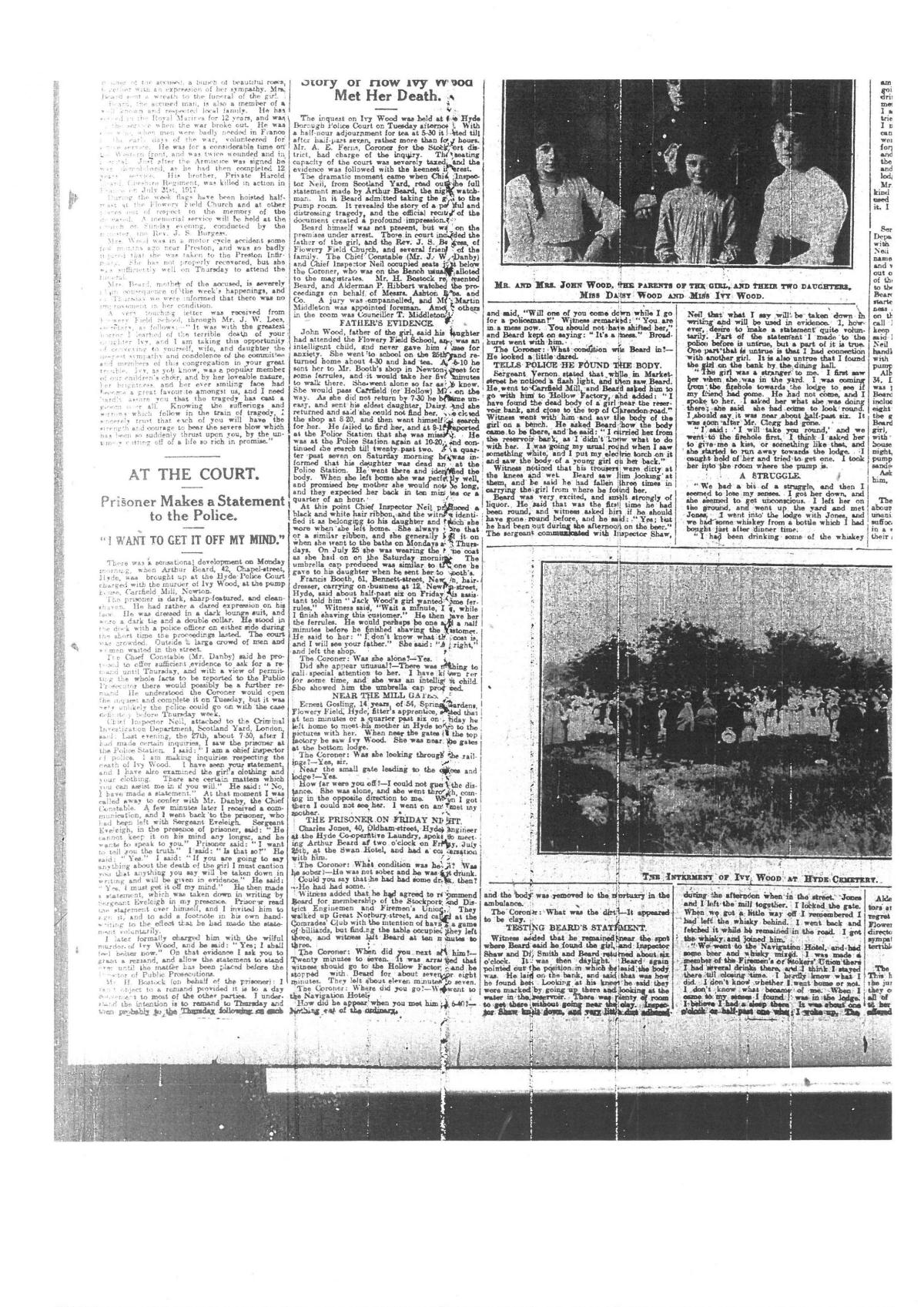

A century later and descendants of the ill-fated victim — 12-year-old Ivy Lydia Wood — some of whom are now living in Bolton, and the inhabitants of the town in which she grew, up are determined not to let the memory of the young girl and her evil attacker be forgotten.

Janet Shaw, one of Ivy’s relatives now living in Bury Road, said: “People have remembered this for years and years. It never went away.”

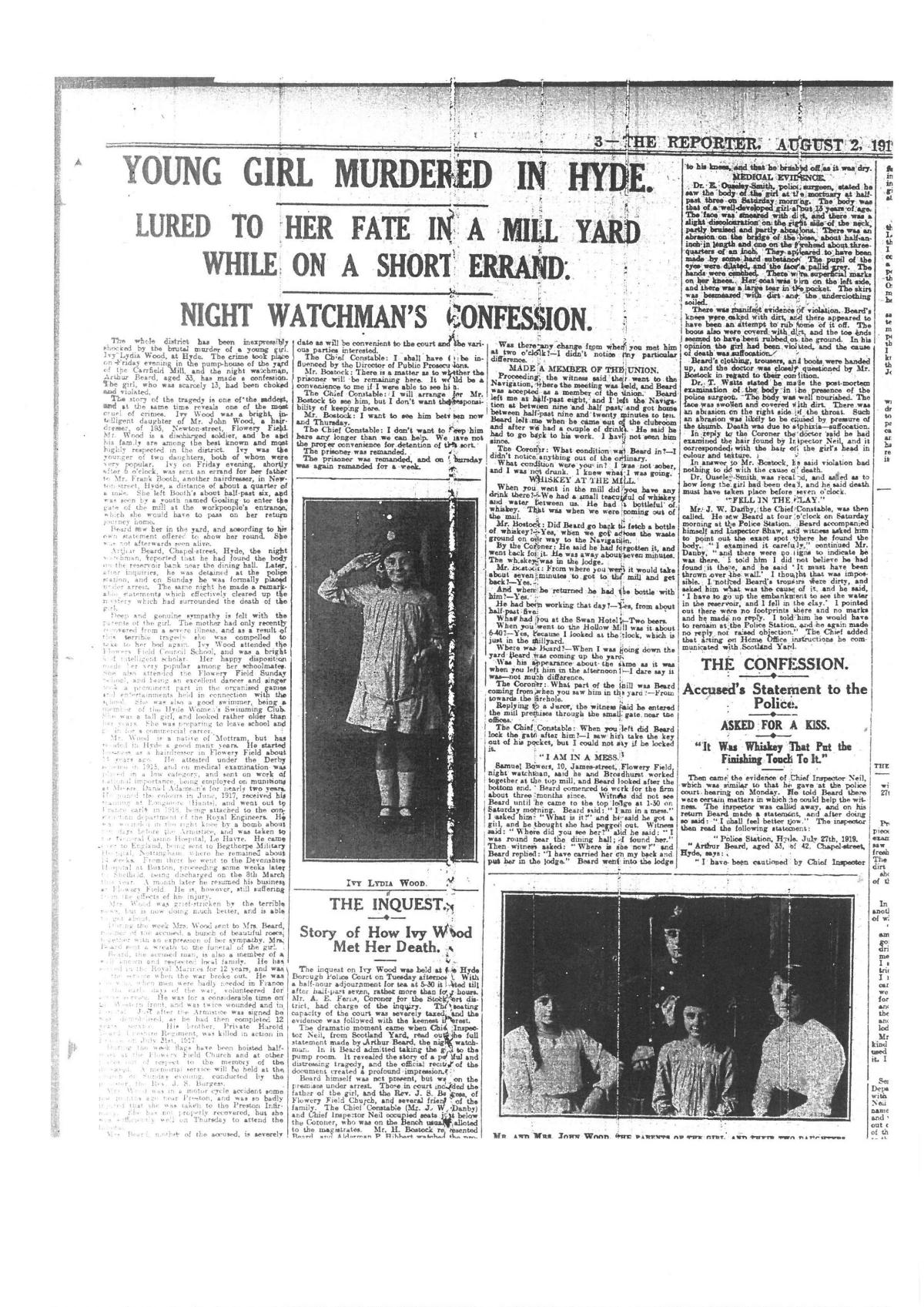

On the afternoon of July 25, 1919, Ivy returned home from school only to be sent out on an errand to purchase umbrella ferrules by her doting father.

As she made her way to the shop of Mr Francis Booth she was seen passing through the gates of Carrfield Mill by a young boy, Ernest Gosling — the last person, except her killer, to see her alive.

Earlier that same day, Arthur Beard, the mill’s 31-year-old nightwatchman took the opportunity to while away the afternoon drinking with his friend, Charlie Jones, at the Great War Comrades Club, before the start of his 6pm to 6am shift.

After going their separate ways the pair were to meet up again at 7pm at the Navigation Hotel for meeting of the Engine and Firemen’s Union, an organisation Beard sought to join.

By 9pm the meeting was over and the newly initiated, and decidedly inebriated, Beard took a final drink with his friend before embarking for work — his alcohol fuelled absence unnoticed.

Shortly after 1.30am the next morning the watchman at a neighbouring mill, Samuel Bower, was rudely stirred from his nap by a frantic and raving Arthur Beard.

The intoxicated Beard told Bower: “I’m in a mess... I have found a girl pegged out... I was in the grounds near the dining room... I carried her back to the lodge.”

Bower followed Beard back to the spot and upon seeing the young girl’s body went in search of a policeman.

He returned with a police constable Vernon who ascertained that the girl had been the victim of a violent assault and had a bloodied face, mussed clothing, and was covered in clay.

Beard’s trousers too had clay about the knees, which when questioned he explained as having occurred when he fell carrying the girl’s body inside.

Police reinforcements arrived, including the chief constable, and when asked about the clay again this time Beard said he had fallen near the mill pond.

This change in his story aroused suspicions and he was taken into custody.

More detectives and officers from Scotland Yard descended on the mill the following day and in an extensive search found critical clues — tiles chipped and splattered with blood, Ivy’s hair fixed in the bloodstains, and mud in the cellar matching that on hers and Beard’s clothing.

Further evidence would turn up in the following days, including the ferrules Ivy had been sent for and the ribbon worn in her hair.

A postmortem examination further found that Ivy had died as a result of suffocation and had been violently sexually assaulted.

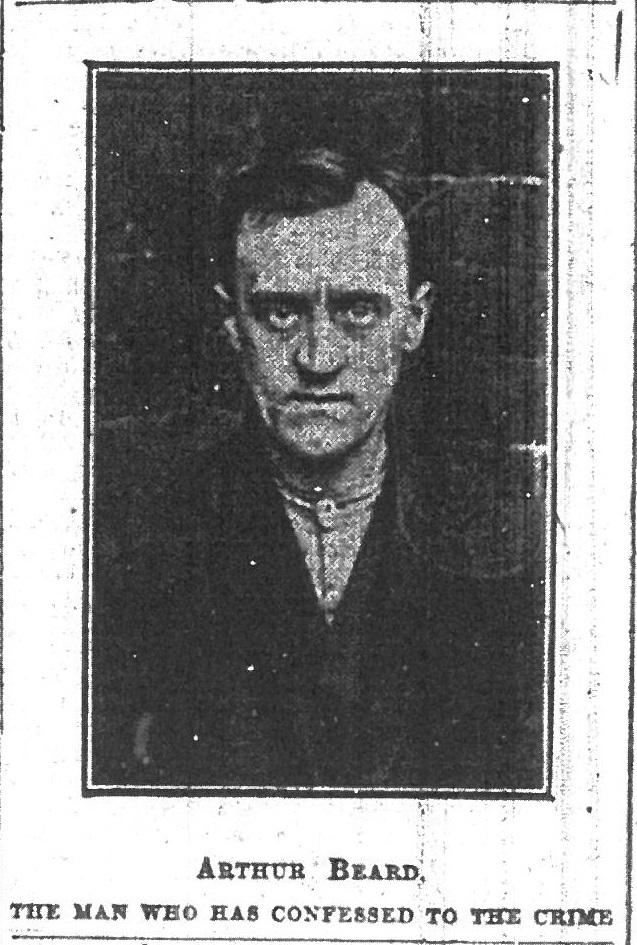

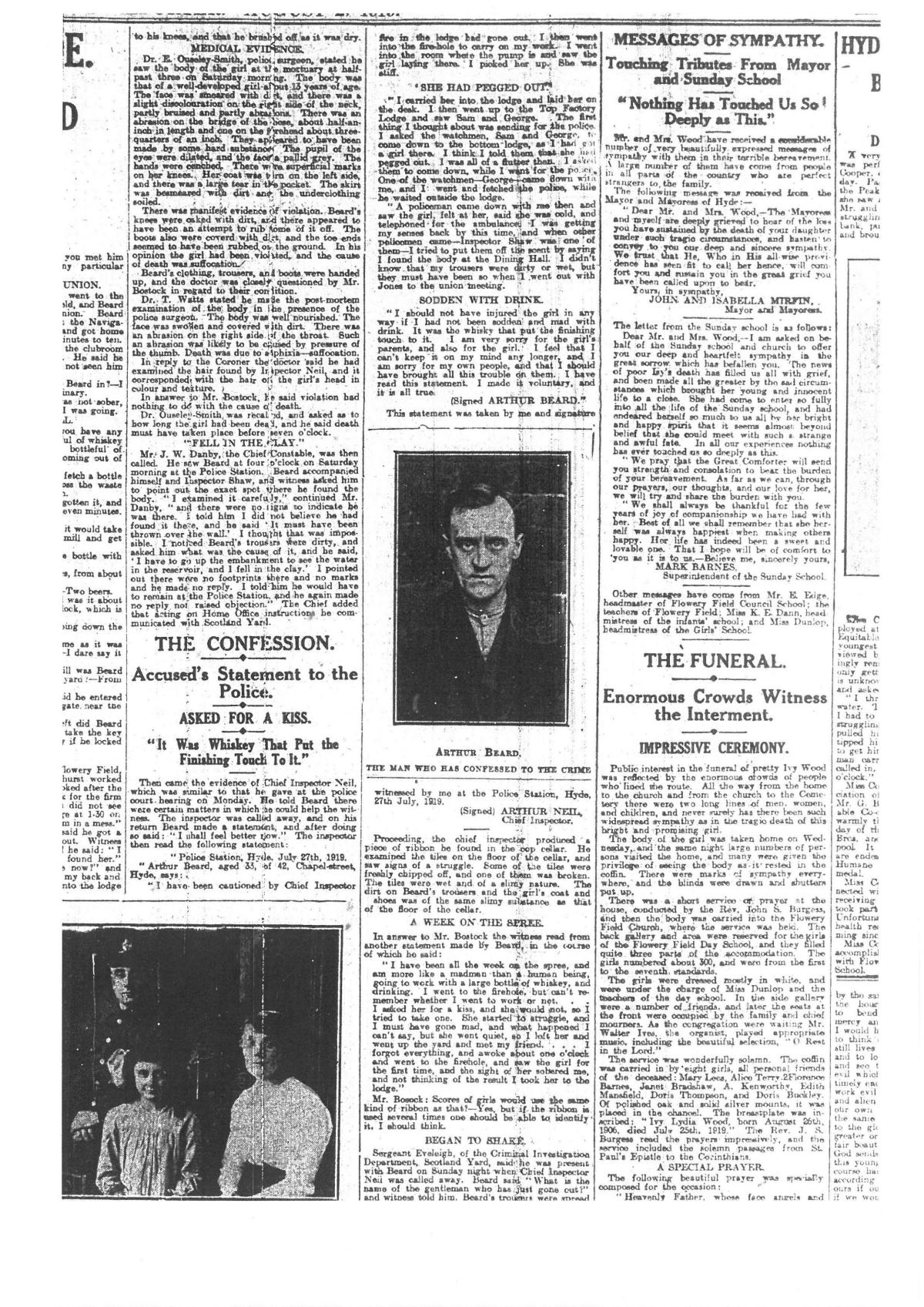

In the meantime, much to the investigating police’s shock, Beard signed a confession admitting to the murder.

Beard stood trial at Chester Assizes some three months later and made his defence that as he was drunk at the time of his crime, his mind was impaired, and therefore where was the ‘malice aforethought’. His counsel argued that based on this his charge should be reduced from murder to manslaughter.

But after three days of hearing evidence, the jury found Beard guilty as charged after just seven minutes of deliberation, and he was sentenced to death.

However, Beard was not going to hang that easily.

His defence counsel launched an appeal which to the astonishment of many was successful. The verdict was changed to manslaughter and the death sentence commuted to life in prison.

A public outcry followed and the case found itself before the highest court in the land, the House of Lords.

There the Law Lords ruled that while Beard may have been too drunk to murder he was not too drunk to form the intent to rape, and as Ivy’s death had resulted from an act of violence carried out during her sexual attack, that the defendant was guilty of murder.

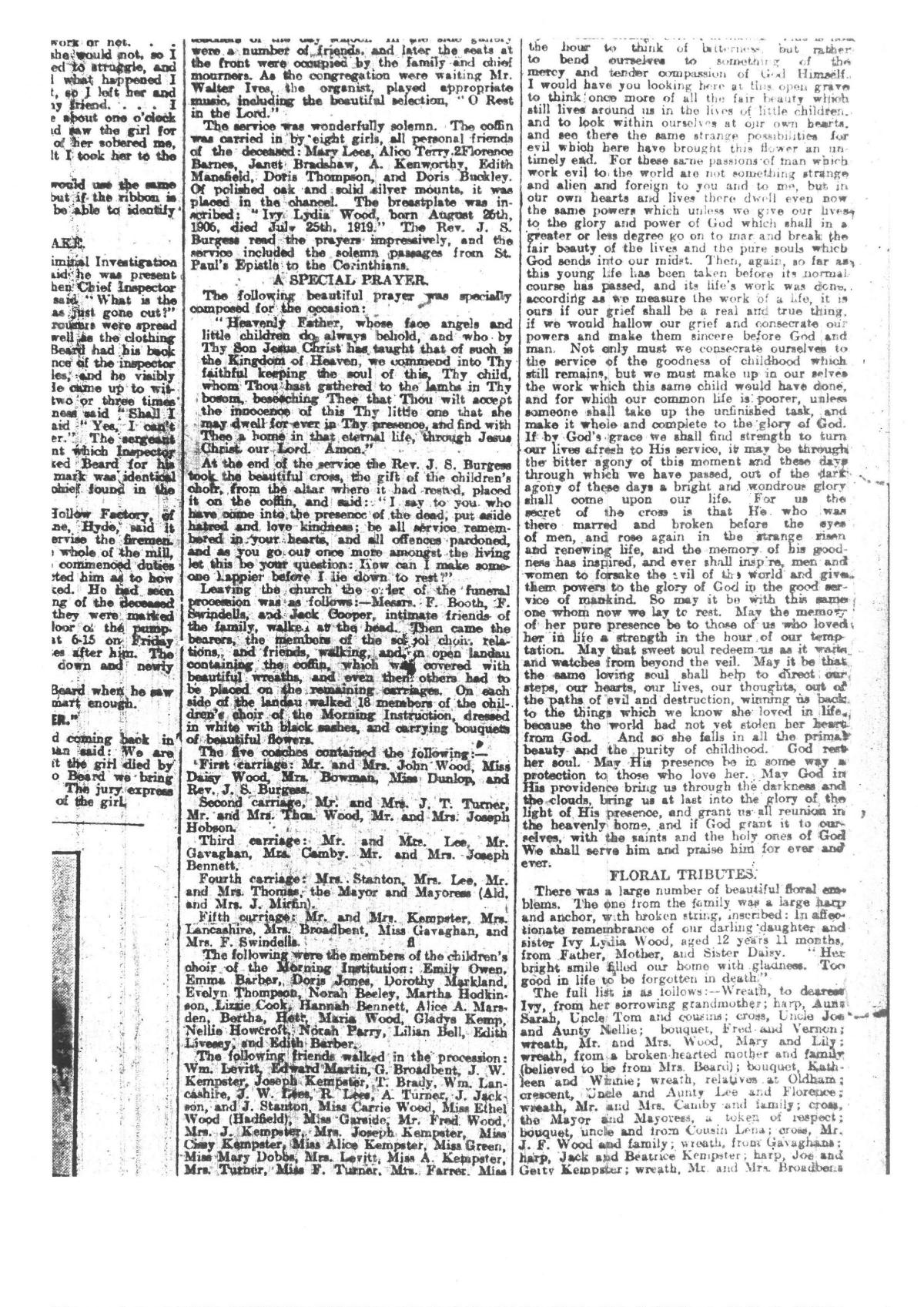

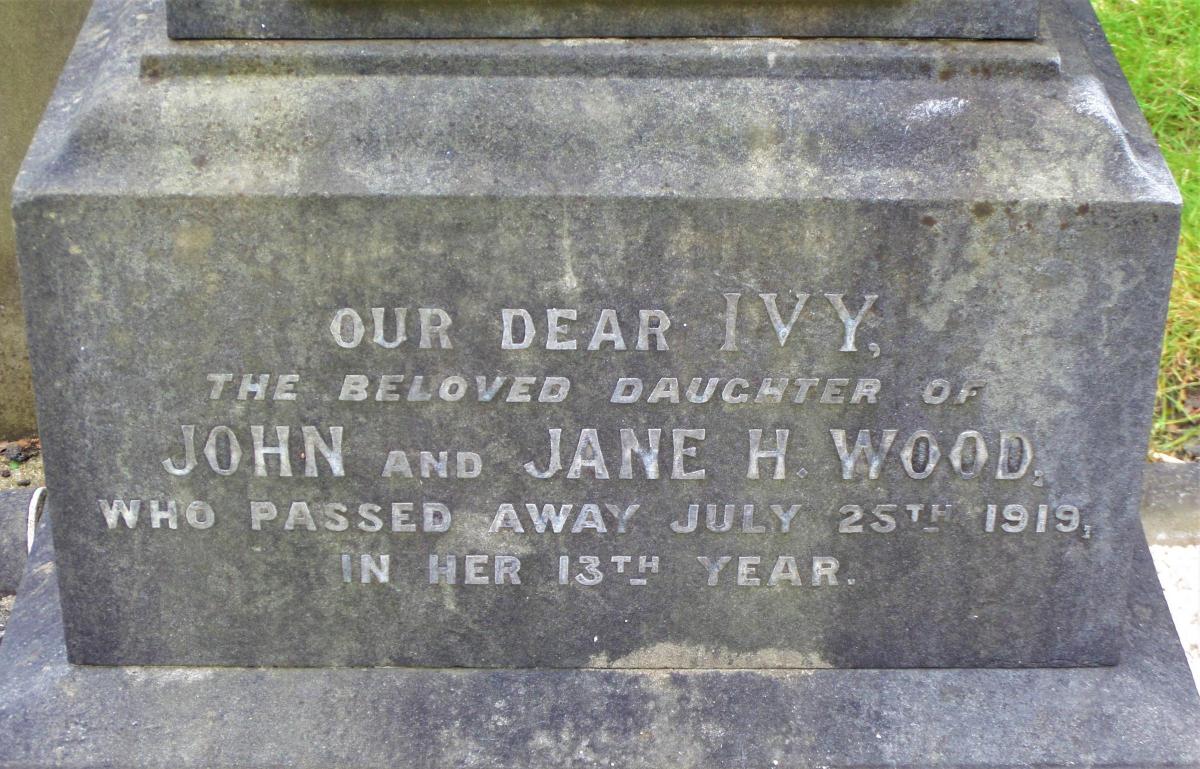

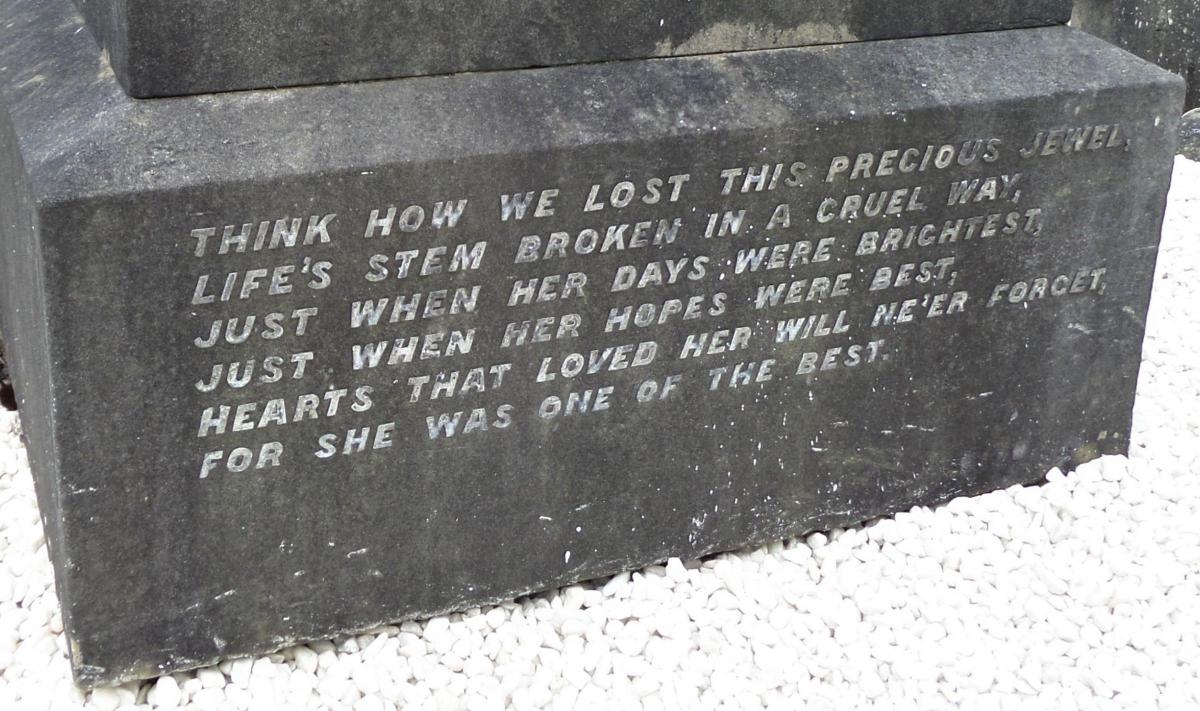

Nevertheless the undeserving Beard was shown surprising mercy and given a reprieve from the hangman and returned to prison to serve his lengthy sentence. In the aftermath of the grisly affair the people of Flowery Field and Hyde rallied to Ivy’s family and her memory. Flags were flown at half-mast, dozens of mourners lined the streets to pay their respects as a funeral cortege processed, and an elaborate gave was erected in Hyde Cemetery.

And this spirit of remembrance has lived on. Exactly 100 years to the day since the horrendous death of Ivy, descendants from both sides of her family returned to her graveside, as many do every year to lay flowers and pay their respects at a moving memorial service.

Ms Shaw said: “Ivy’s story has lived with me since my mother first told me as a teenager. But it has brought us together as a family.

“She never had a chance to have her own family or her own children and it’s so sad that she was denied all that. I still find it upsetting. You just wish you could go back to the gates and tell her never to go into that mill.”

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel