In the latest of a series of articles for Looking Back, Paul Salveson looks back to when coal was king. Paul is an historian and writer and lives in Bolton. He is a visiting professor in WorkTown Studies at the University of Bolton and author of several books on Lancashire history

Bolton is best known as a cotton town, but coal mining was once an important local industry. It fed the mills, factories and loco sheds when steam power drove industry. Most of the collieries in the Bolton area were small and few survived into the 1960s.

Yet Bolton was the regional centre of the miners’ union and its fine offices still survive. Within a few miles of Bolton town centre some of the biggest and most modern pits of the Lancashire coalfield lasted into the early 1990s.

Coal mining in the Bolton area goes back centuries. In 1538 the traveller John Leland commented on the burning of coal and turf in the area. Two centuries later Daniel Defoe described the mining of ‘cannel’ coal in the Westhoughton area.

Signs of early coal mining abound around the fringes of Bolton. The continuation of Smithills Dean Road after it crosses Scout Road is ‘Coal Pit Road’, which was the route of the Winter Hill ‘mass trespass’ of 1896. The lane served Holden’s Colliery which worked the Sandrock, or Mountain Mine on the slopes of Winter Hill. Along Scout Road itself there are cottages called Colliers Row and New Colliers Row.

There were many small coal pits dotted around Turton and the north side of Bolton, most of which were worked out over a century ago. However, Montcliffe Colliery, off George’s Lane, Horwich, survived until 1966 and Scot Lane pit in Blackrod was still operating in the 1950s.

Westhoughton, Farnworth and Little Lever had richer deposits and the Manchester, Bolton and Bury Canal served several pits along its route through Darcy Lever and Little Lever, including Ladyshore Colliery, remains of which are still visible from the towpath.

Great Lever Colliery occupied the site of what became Bolton’s greyhound track on Manchester Road and was connected to the Bolton-Manchester railway by a short branch line. Victoria Colliery, Hunger Hill, closed in 1960 and the site is now a garden centre.

As Bolton’s mills and factories expanded in the early nineteenth century, the demand for coal was insatiable. Bolton’s first railway, the Bolton and Leigh, opened in 1828 and one of its main functions was to bring coal from the Leigh and Atherton pits to Bolton.

The bigger collieries were owned by major landowners, such as the Duke of Bridgewater, the Earl of Balcarres, the Hultons and Fletchers.

Andrew Knowles, born in Turton, started his mining career running the small family pit near Edgworth but expanded into large-scale deep-mining in the richer coalfields around Farnworth and Salford in the mid-nineteenth century. Many of the coal companies merged in 1929 to form Manchester Collieries Ltd.

In 1880 the Mines Inspector reported a total of 534 coal pits in the Lancashire coalfield. There were 10 pits in Blackrod, 19 in Bolton, 18 in Farnworth and Kearsley, three in Harwood, six in the Horwich and Rivington area, three in Harwood, were seven in Middle and Over Hulton, 28 in Darcy, Great and Little Lever and 16 in Westhoughton.

Life down the pit was hard and dangerous. Explosions and roof collapses were frequent and conditions were appalling. Children and women were still working underground until it was outlawed, for all women and children under the age of 10, in 1842. Women continued working on the surface – the ‘pit brow lasses’ - until much later.

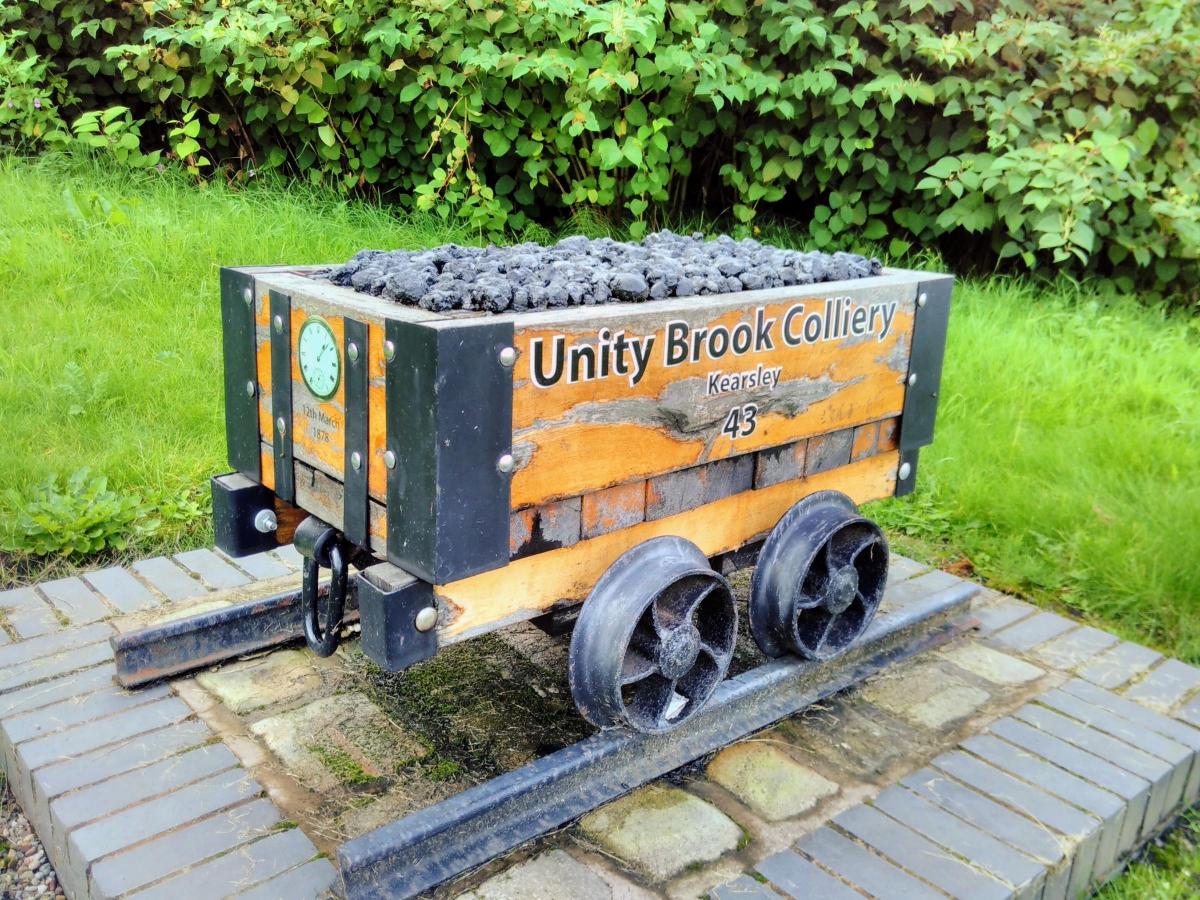

The Bolton area experienced one of the worst disasters in mining history. On December 21, 1910 ,the Pretoria Pit, Westhoughton, blew up. A total of 344 men and boys perished. An earlier disaster on March 12, 1878, occurred at Unity Brook Colliery, between Kearsley and Clifton, when 43 miners were killed. Both events are commemorated to this day by their local communities and schools.

These were not isolated incidents; the Unity Brook tragedy was the third of series of major accidents occurring in the Bolton area in the mid-1870s.

The Lancashire miners made spasmodic attempts to form unions from the 1830s. The Friendly Society of Coalmining was formed in Bolton in 1830. Unions were strongly resisted by the owners and it wasn’t until the second half of the nineteenth century that trade unionism put down lasting roots.

The most outstanding figure in Lancashire mining trades unionism was Thomas Halliday, a Little Lever miner who struggled to bring together a number of small, localised unions into one strong body. Eventually, the Lancashire and Cheshire miners became part of the Miners’ Federation of Great Britain, later the National Union of Mineworkers.

They chose Bolton as its headquarters, with a fine building designed by local firm Bradshaw Gass and Hope and opened in 1914 on Bridgeman Place. It remains to this day, owned by Greater Manchester Chamber of Commerce. The chamber has exciting plans to develop the mining heritage features of the building.

Some of the companies were better employers than others. Fletcher, Burrows – based around Atherton – was one of the more progressive and was the first in Britain to introduce pit-head baths.

One of the most remarkable engineering achievements of the industrial revolution was the network of underground canals developed, from 1760, to serve the pits on the south side of Bolton. The entry point into the system was at Worsley Court House and ‘the delph’ is still visible.

The canals, on different levels, extended as far as Daubhill and Farnworth and are still there, abandoned, today. The ‘main navigable channel’ runs more or less parallel beneath Plodder Lane.

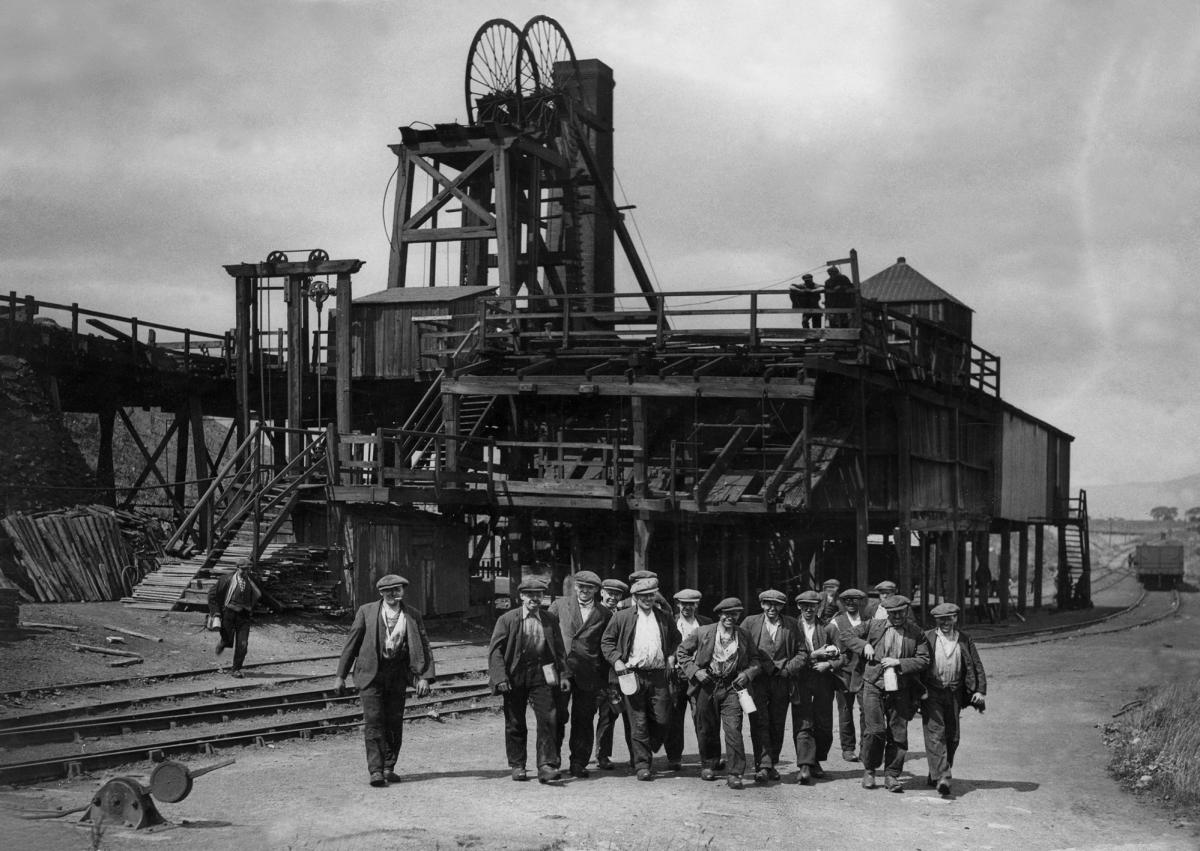

After the Second World War the demand for coal continued to be high. After nationalisation in 1947, several collieries had major investment including Mosley Common, Agecroft and Parkside, near Newton-le-Willows. The older pits were closed. Astley Green Colliery, sunk in 1908, shut in 1970 but is now a museum. It’s well worth a visit.

Industrial relations in mining improved following nationalisation. However, the industry was hit by major strikes in 1972 and again in 1974 which led to the toppling of the Heath Government.

It was a dress rehearsal for an even bigger conflict in 1984-5. The issue wasn’t about pay, but the National Coal Board’s pit closure programme.

The National Union of Mineworkers leadership voted to strike but not all of the districts went along with the decision, the traditionally moderate Lancashire area being one of them.

The strike was long and bitter. Ultimately the Coal Board, backed by the Thatcher Government which demonised the miners as ‘the enemy within’, won.

The programme of pit closures accelerated and by the early 1990s deep mining in Lancashire was at an end.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel