Professor Paul Salveson is a historian and writer and lives in Bolton. He is visiting professor in Worktown Studies at the University of Bolton and author of several books on Lancashire history

A fascinating aspect of Bolton’s role as a major centre of textile engineering was its strong links with pre-revolutionary Russia. During the second half of the 19th century Bolton engineering firms helped to equip Russia’s emerging cotton industry. It wasn’t just machinery that Bolton exported – it was also people. The story has yet to be told in full, but this article is a start, which I hope will stimulate further recollections from readers who may have had family connections with Russia.

Russia in the 19th century was an autocratic state ruled by the Romanov dynasty. In the 18th century both Peter and Catherine the Great had used the state as a means of promoting industrial development, with textiles as a key lever. However, much textile production remained small scale with spinning and weaving mostly done by hand, using serf labour.

Alexander II (1818-1881) attempted to bring in reforms and industrialisation, following his accession to the emperor’s throne in 1855, after Russia’s defeat by Britain and her allies in the Crimean War. His outstanding achievement was the abolition of serfdom in 1861, emancipating 23 million serfs. Yet many opponents saw it as ‘too little, too late’.

He was assassinated in 1881 and his successor, Alexander III, battened down the hatches and pursued a conservative approach, continued by his son Nicholas II. The 20th century saw Russia in the throes of revolution in 1905, which was suppressed by Nicholas. However, this was only a prelude to the sensational events of 1917 when, after the abdication of Nicholas in February 1917 and the election of a Provisional Government, the left-wing Bolsheviks, led by Lenin, took control in the ‘October Revolution’ of that year.

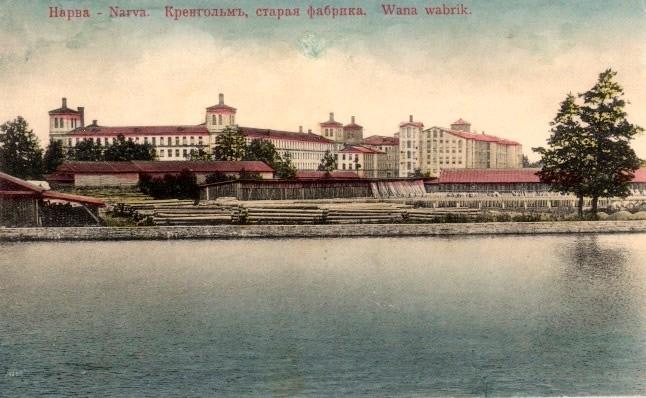

Alexander II was keen to industrialise parts of his vast empire and state support for a Russian textile industry was seen as a means to force an industrial revolution. To a certain extent, his strategy worked and despite the political upheavals of the nineteenth and early twentieth century, Russia’s textile industry grew to become the fourth biggest in the world – after Britain, the United States and Germany. And it was largely down to the expertise it used from Lancashire.

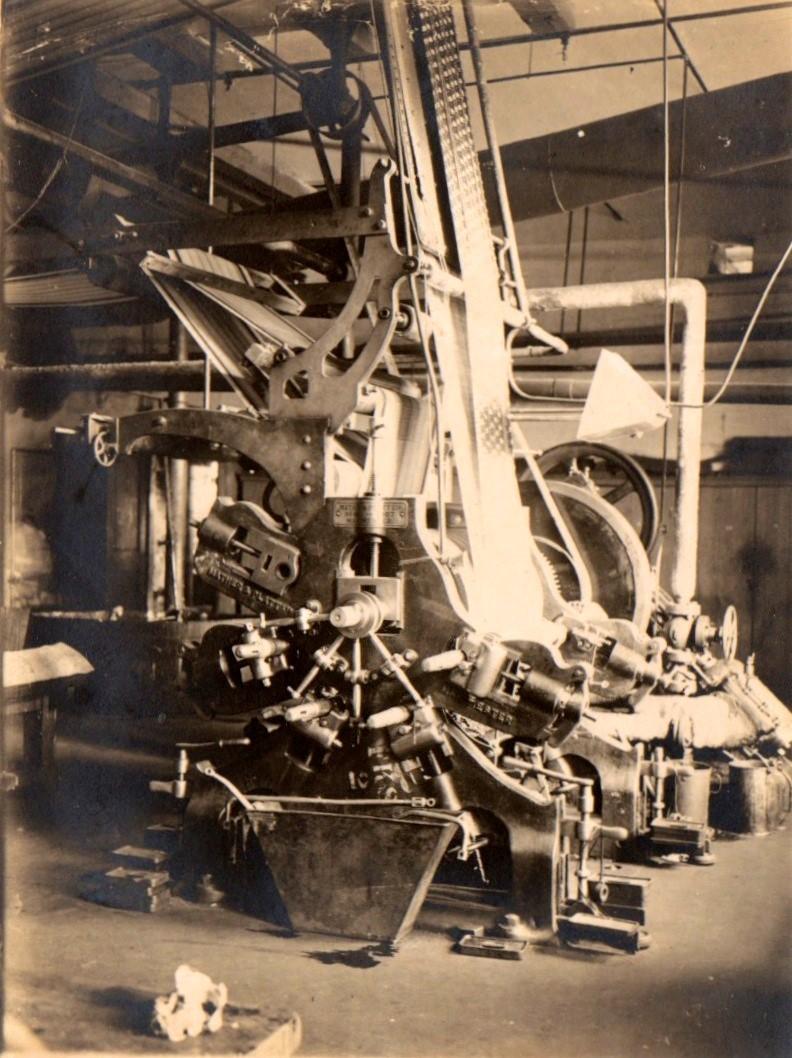

Russia developed what became known as ‘technology transfer’ using British engineering to equip and run the growing number of cotton mills in Russia. The key figure in making this happen was Ludwig Knoop who acted as an intermediary between the Russian authorities and Lancashire-based textile engineering companies. These included Oldham-based Mather and Platts and Howard and Bullough of Accrington.

However, Bolton-based firms Hick Hargreaves, John Musgrave and Sons and Dobson and Barlow all developed strong links with Russia’s cotton industry. This involved much more than shipping out steam engines and boilers to power the mills.

Expertise was in short supply and firms such as Hicks and Musgraves sent out skilled engineers for extended periods of time – with some actually becoming adopted Russians. Ivanovo, about 100 miles north-east of Moscow, became known as ‘the Manchester of Russia’ and developed as a major cotton manufacturing centre.

Scores of Bolton families, with many fellow Lancastrians from Oldham, Accrington and Rochdale, went out to Russia. They set up their own social clubs in places like Ivanovo. Much of their history is lost but some family records have survived.

Robert Crompton was born in Bolton in the 1840s and became an apprentice in one of the Bolton mills. He rose to the ranks of overseer and qualified as an engineer. In the 1850s He was asked by his firm to travel to Kiev to help establish a mill that had installed machinery that he was familiar with. It was clearly seen as an extended job and he made the difficult journey to Russia with his young wife Ann.

His great grand-daughter Dorothy says that “he worked at the mill, creating a strong friendship with the mill owner and was respected by the workers.”

The Cromptons had four children, all born in Russia. Two died young and were buried in Odessa. The third, Mary Alice Crompton, was brought up in Kiev and could only speak Russian until the age of five, when the family returned to Bolton in the 1870s. There were concerns for the family’s safety owing to growing political and industrial unrest in the country.

The family moved into a house on Hulton Lane but their return was short-lived. Not long after the mill owner in Russia asked Robert Crompton to come back to help him at the mill - being a good friend, he did. However, he quickly succumbed to illness and died soon after his return. He is buried with his two children in Odessa.

Another fascinating link is through the family of Bolton suffragette Sarah Jane Carwin who was born in Bolton in 1863. Her father, John, was an engineer and in 1866 the entire family sailed to St Petersburg though it isn’t clear where John and his family settled.

However, his wife Jerusha died shortly after their arrival. John re-married a Russian girl. They were wed in ‘the chapel of the British factory’ at St Petersburg and returned to Bolton in 1874.

The reference to ‘the chapel of the British factory’ also raises some Bolton connections, through the Bolton architect Richard Knill Freeman. He was commissioned to design the only Anglican church in Moscow, which was built specifically for British ex-pats in the city, in 1884.

Knill Freeman knew John Musgrave, the owner of the engineering firm which supplied many Russian mills with machinery. It is possible that Musgrave helped Knill Freeman win the contract to build the church which was located near to some of Moscow’s largest mills. He also designed a house in Moscow which bears similarities with Smithills Hall!

The ex-pats were well paid for their skills. Articles of agreement signed in 1899 between Bolton firm John Musgrave and Sons with Moscow-based De Jersey & Co. for the engineering services of William Fisher give his wages as £6 a week, as well as £15 for travel costs to and from Russia.

An engineer called Smith worked for Hick Hargreaves and went out to work in the Russian mills in the 1870s. He married there in 1876 and had three children who were born and raised there, only coming to England when revolution was looming. One of the boys won an apprenticeship at Hicks and returned to Russia after marrying a Bolton girl who went with him.

The story of Bolton’s connections with the American poet Walt Whitman are well-documented; but there is a Russian connection here as well. The leader of the group of Bolton Whitmanite enthusiasts was J W Wallace who lived with his parents on Eagle Street, in The Haulgh. His father was a millwright who spent extended periods working in the Russian mills for one of the large Bolton engineering companies.

Lancashire cotton men can take the credit for introducing football to Russia. The first competitive and regular football games in Russia started in the textile town of Orekhovo-Zuevo, about 50 miles east of Moscow. The area saw a huge boom in textile production in the 1840s, with the Morozov family being the dominant employer.

The firm invited engineers and managers from Lancashire To maintain the machinery and they brought football with them. At first, they played among themselves, or against teams of British engineers from the Hopper Factory in Moscow. Chorley-born Harry Charnock was managing director at the Nikolskoye Textile Factory near Orekhovo-Zuevo.

In the 1880s he began to organise regular matches, involving Russian players as well as Englishmen. He became the vice-president of the Moscow Football League. Whilst in Russia he met and married Anna Hedwig Schelinsky; they had two sons.

A Christmas postcard has survived written from a family in Breightmet to a ‘Mr and Mrs Ashcroft’ living in Orekhovo-Zuevo in the early 1900s. Other family recollections include those of Tim Baines whose great-grandfather went out to Russia with his wife to work in the mills but returned just before the revolution of 1917.

The connections between the Russian textile industry and Lancashire came to an abrupt end after the revolution, though by then the industry was well established. There are records of an ‘Olga Snape’ who was born in Russia but who came to Bolton at the time of the revolution, almost certainly having family connections in town.

However, some Bolton people had put down deep roots in Russia and it is likely that some remained after 1917. It would be fascinating to know more; I suspect this account is just the tip of a very large iceberg.

I am very grateful for the assistance of Pamela Smith (www.drawnground.co.uk), Dorothy Douglas and her family, Barbara Simpson, Nora and Joseph Morris, Rita Greenwood and Steve Brown.

For details of Paul’s new book Moorlands, Memories and Reflections, featuring different aspects of Bolton’s history, visit www.lancashireloominary.co.uk

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel