Professor Paul Salveson is a historian and writer and lives in Bolton. He is visiting professor in ‘Worktown Studies’ at the University of Bolton and author of several books on Lancashire history

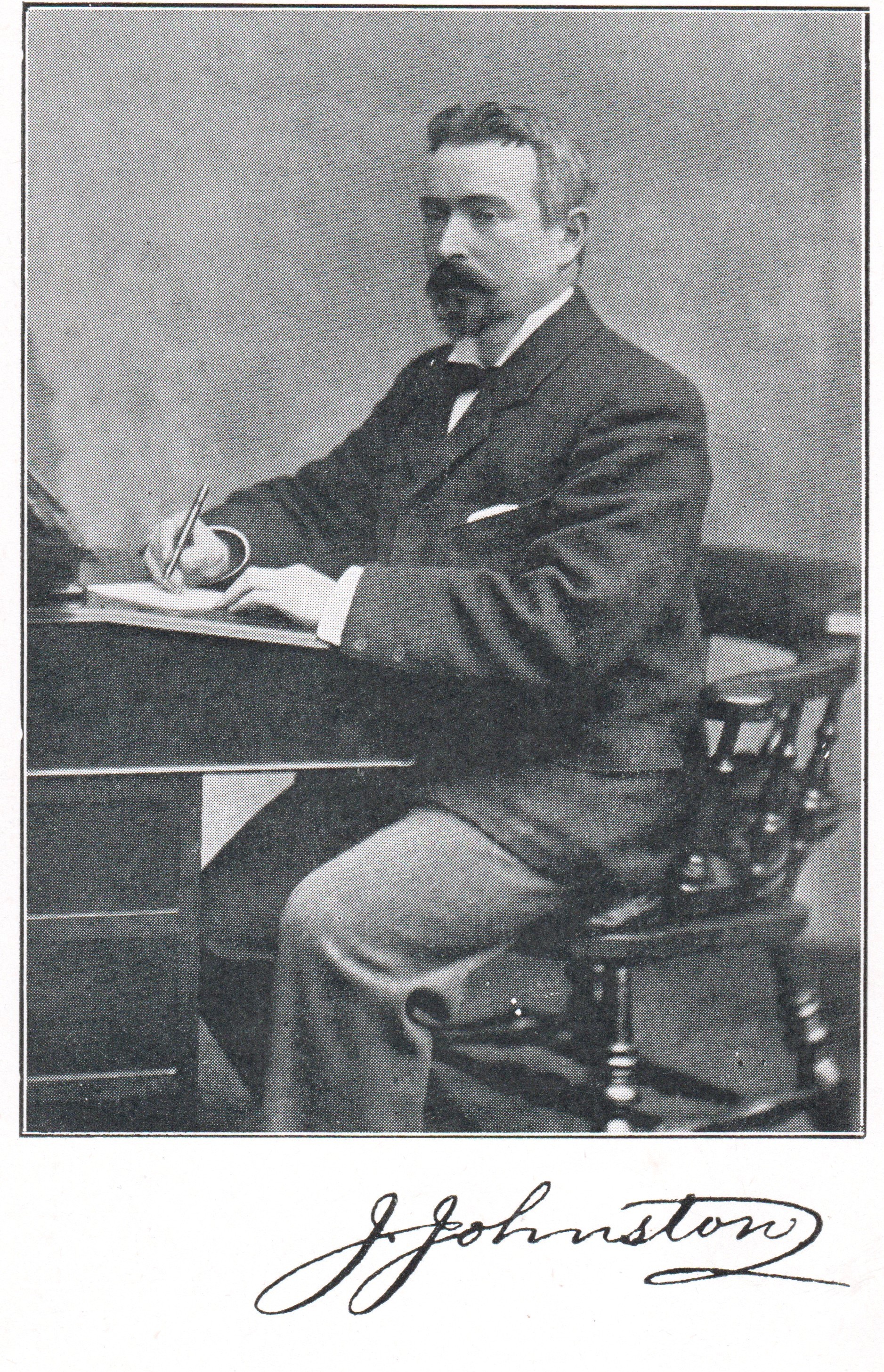

One of the most remarkable figures in Bolton life in the years before the First World War was Dr John Johnston. He was a man who wore many hats – doctor, poet, cyclist, traveller, photographer and more.

Bolton writer Allen Clarke described him as “one of our local bards and a great bicycle traveller who has issued many books and pamphlets.” He was one of the main figures in Bolton’s Walt Whitman Fellowship’ known colloquially The Eagle Street College, along with his good friend J W Wallace (known as The Master).

Johnston was a proud Scot, born in Annan, Dumfriesshire, in 1852. He moved to Bolton in 1876 as a GP, after having qualified as doctor at Edinburgh in 1874 followed by a two year stint as hospital surgeon at West Bromwich. He lived initially at 2 Bridgeman Street before moving to 54 Manchester Road.

Signed photo of Dr John Johnston

Johnston was a highly skilled physician and as well as his ‘day job’ as a GP he found time to be an instructor for the Lancashire and Yorkshire Railway’s ambulance classes. This brought him into direct contact with the realities of daily life on Britain’s railways, and the dangers faced by railwaymen.

In his diary for 1887 he records the death of a shunter at Trinity Street station, William Davies. He fell off a truck and was run over – both his legs were broken and his left foot was cut off. He died from his injuries:.

Johnston wrote: “The poor fellow was one of the members of my ambulance class and has left a wife and five children. Alas! Alas!”

In addition to his work as an instructor for the railway ambulance classes he acted as a judge at many railway ambulance competitions, including those of the London and North Western and Great Central Railways. These contests were major events which continued well into the 1960s but have sadly died out.

During the First World War he served at the vast Whalley Military Hospital before moving on to Townley’s Hospital where he was appointed Medical Superintendent in September 1917.

An aerial view of Townleys Hospital, November 1935

In Moorlands and Memories Allen Clarke writes of Townley’s Hospital during the First World War, still a very recent memory, and how “many boys in the characteristic blue suit of the wounded and invalid soldier have sat on the seats at the Great Lever tram terminus, close to Townley’s Hospital.”

In Johnston’s diary there is a particularly moving entry where he describes a soldier pleading with him to amputate his hand so that he wouldn’t have to return to his regiment.

Johnston records that: “We decided that to attempt its removal might involve some risk to the future usefulness of his hand and we therefore counselled it being left alone.

‘Danger or no danger’ said the soldier to me, ‘I want you to do the operation, I’d rather lose my hand than go back yonder’. He meant The Front – ‘it’s Hell!”

Townley’s Hospital was built next to The Fishpools Institution – the workhouse, a name to strike fear into working class people in Bolton.

However, the footpath to the workhouse was not without its charms; it can still be walked or cycled today.

The ‘ginnel’ ran from Rishton Lane alongside the former railway. They were still there in the 1960s but have gone now.

The path was known as ‘Lovers’ Walk’. Allen Clarke recalls: “Sometimes I have seen workhouse inmates on this path, returning to the place after an afternoon out, pass lovers loitering along oblivious of everything but their paradise, perhaps never thinking that once upon a time some of these old pauper men and women were young and in love like them.”

Today, the path forms part of a national cycleway Route 55.

Johnston would have been a great champion of cycle networks. A hundred years ago there wasn’t really much need for segregated cycle routes as motorised traffic was very limited.

One of the few positive outcomes of the current pandemic is that people have got their old bikes out, given them a rub-down and a bit of oil, and rediscovered the pleasures of cycling on quiet roads. I hope it lasts, but there’s no doubt we will need our ‘off road’ routes, and many more of them.

Johnston was a great enthusiast for the bike and ventured into poetry to extol its virtues:

“Hurrah for the Cycle, swift, trusty and strong!

May it daily win loves and stay with us long!

Good luck let is wish to the Courser of steel,

And Health and Long Life to the Men of the Wheel!”

As well as a practical way of getting around, he recognised cycling as a means to health and well-being. His poem ‘Doctor Air’ tells us:

“There’s Dr Blister, Dr Bleed, and old-fashioned Dr Pill,

Who with mixtures, potions, draughts, will cure your every ill;

And Dr Sanitation will with wonder make you stare,

But the king of all the doctors, new or old, is Doctor Air”

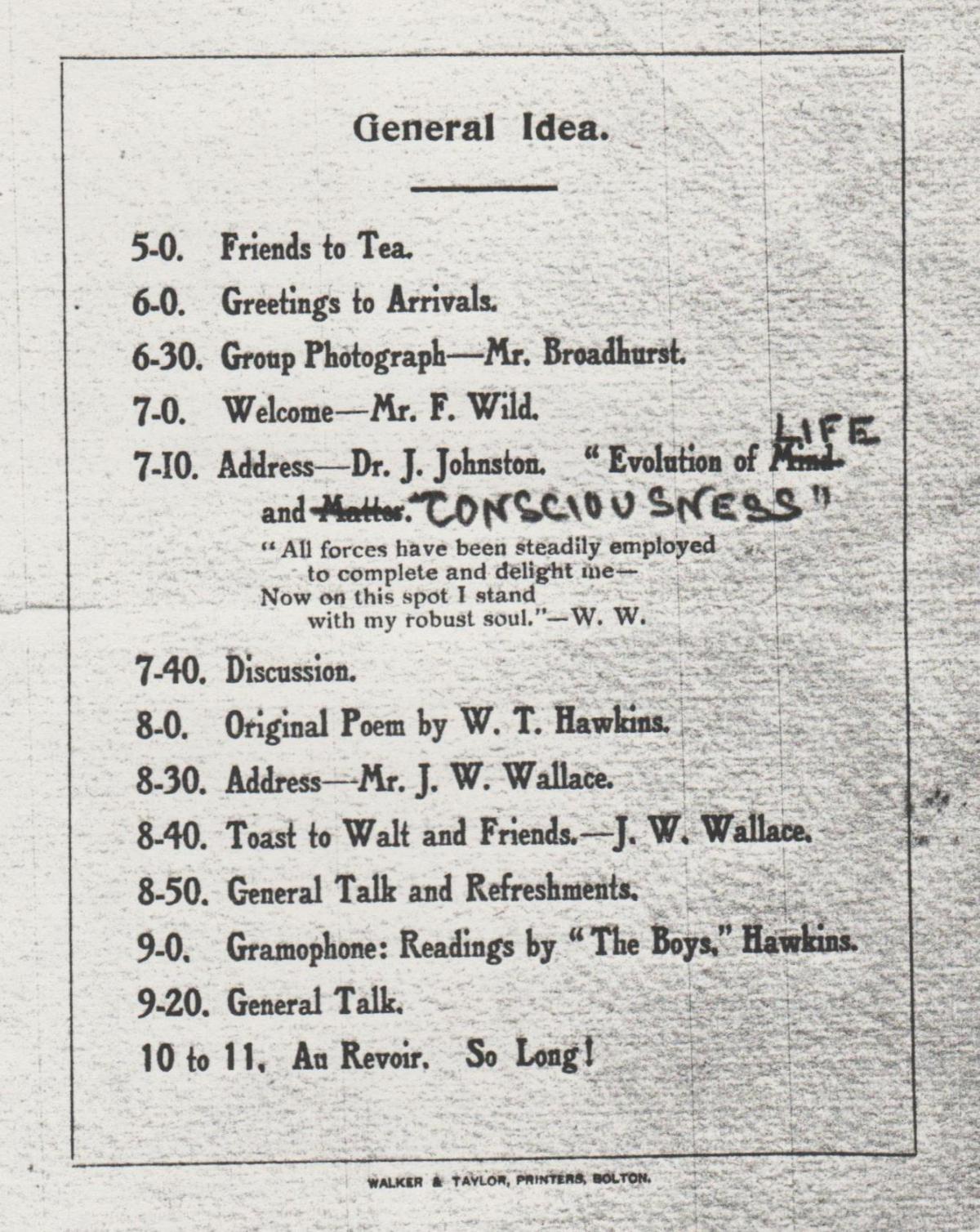

Johnston’s poetry was published in 1897 as Musa Medica. The book of poems was dedicated to “The Master and the boys of The Eagle Street College, from whom so many of these songs and verses received their initial impulse...”

The collection included ‘The Song of the Eagle Street College’ written in Scots dialect.

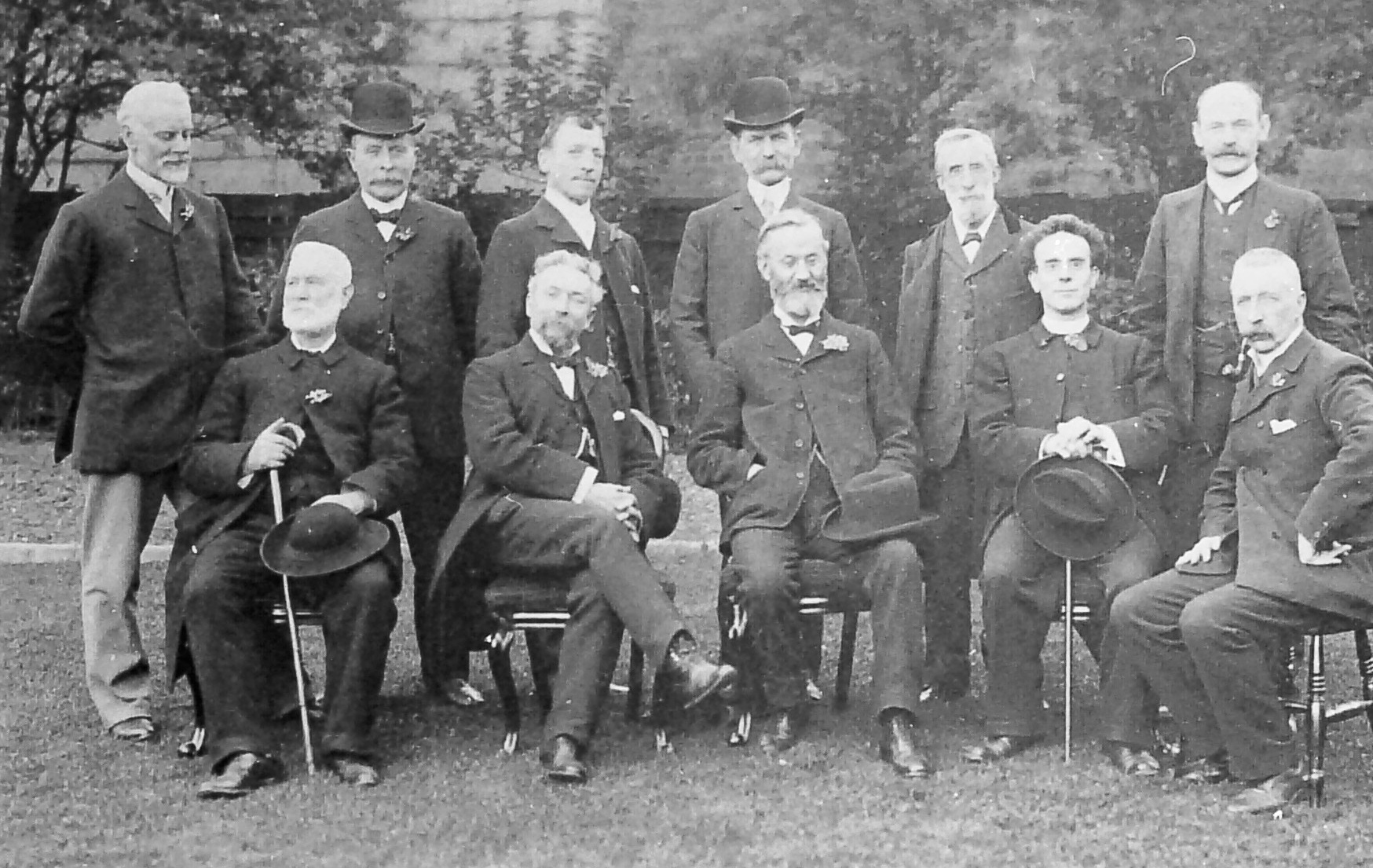

John Johnston with J W Wallace, the Master, and the Eagle Street College

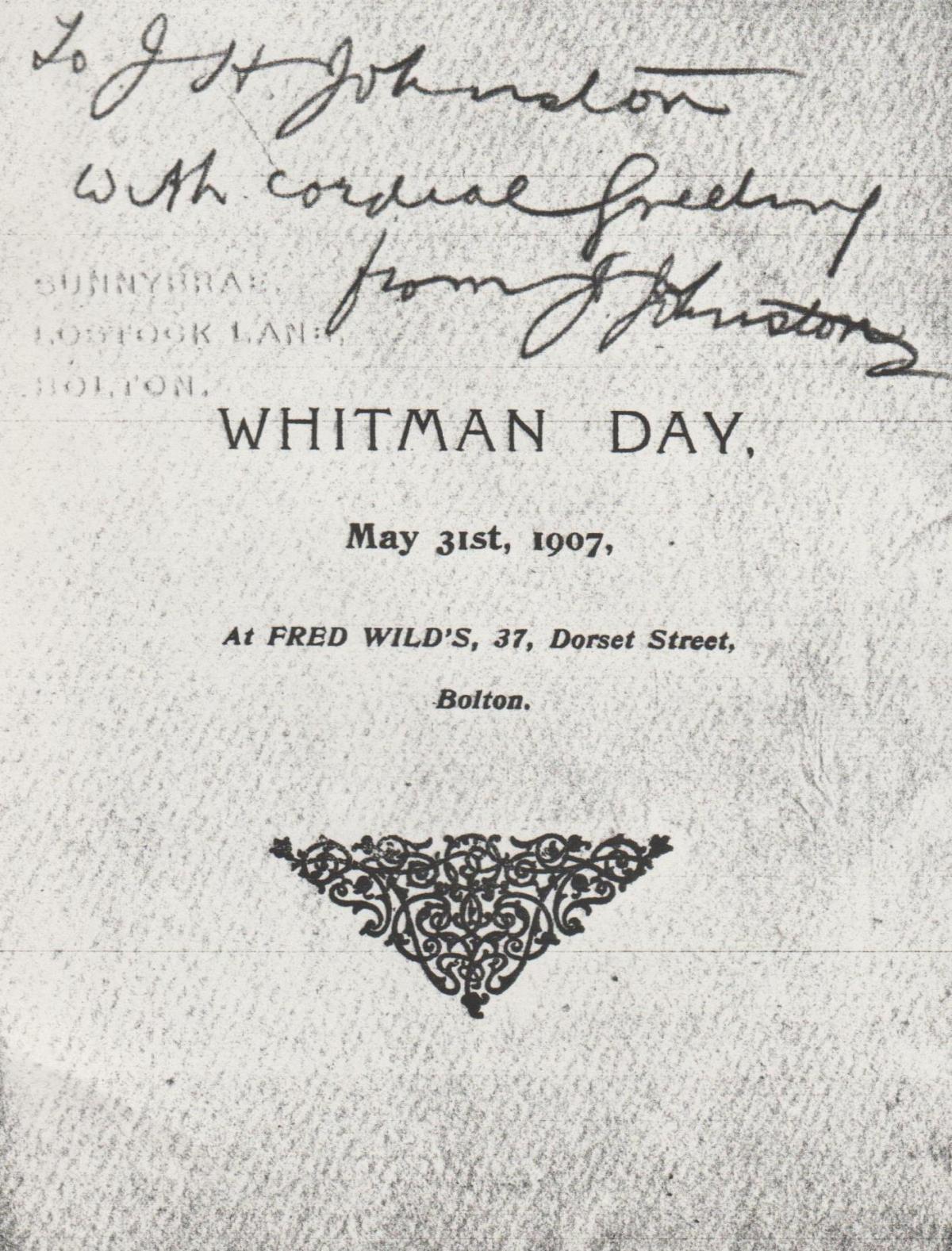

Johnston, J W Wallace and a handful of other friends such as cotton waste merchant Fred Wild formed the basis of ‘The Eagle Street College’.

They met in Wallace’s house in The Haulgh to discuss Whitman’s poetry and philosophy and began a correspondence with the poet which lasted to Whitman’s death in 1892.

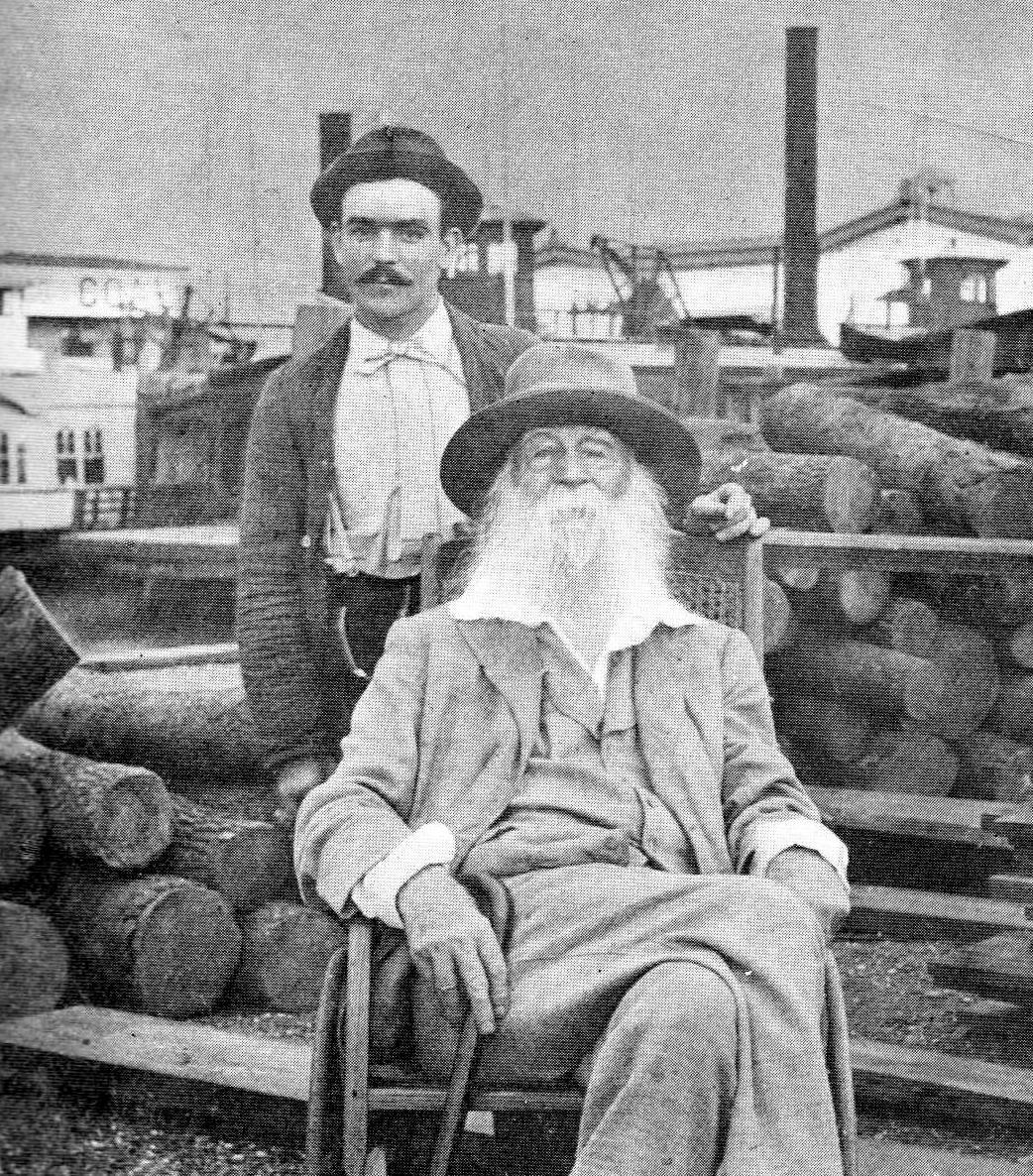

Walt Whitman with his carer Warry Fitzinger in a photo taken by John Johnston in Camden Wharf, New Jersey in 1890

Johnston visited Walt Whitman in New Jersey in 1890, to be followed by Wallace the following year. His impressions, including his professional-standard photographs, were published in book form. He met Whitman within hours after he had disembarked after his trans-Atlantic crossing. It was an amiable conversation.

The poet told him “That must be a very nice little circle of friends you have at Bolton. I hope you will tell them how deeply sensible I am of their appreciation and regard for me....”

After Whitman’s death Johnston stayed in touch with many of his American friends and amassed a large archive of papers which were donated to Bolton Library.

In the early 1900s Johnston and his wife Bertha moved to Lostock, a pleasant spot convenient for his other preferred form of transport – the train. From the early 1900s he gives his address as ‘Sunny Brae’, Lostock Junction Lane. The fine Edwardian house still stands.

I wonder if the present occupants know that their home hosted many of the garden parties, where excerpts from Leaves of Grass were read, Whitman’s ‘loving cup’ with spiced claret being passed around, followed by speeches from ‘the master’ Wallace and often Johnston himself.

The name of Dr Johnston crops up in many accounts of ‘civic’ activities in Bolton between the 1880s and First World War. He was active in the early Independent Labour Party and Labour Church but also played high-profile roles in a range of local institutions, including Bolton Lads’ Club, civic societies and numerous medical associations.

He chaired a meeting of Bolton’s Progressive League and Housing and Town Planning Society at New Spinners’ Hall (St George’s Road) in October 1912 when Edward Carpenter spoke on Beauty in Civic Life.

There was a strong lobby in Bolton and elsewhere to ‘beautify’ industrial towns (Oldham had its ‘Beautiful Oldham Society’). Johnston was active in Bolton’s Housing and Town Planning Society which hosted the lectures by landscape architect T.H. Mawson on ‘Bolton as it is and as it might be’.

He was strongly opposed to child labour, sharing Clarke’s outrage at the half-time system which still operated in the Bolton mills at the turn of the century.

His book Wastage of Child Life (1909) was a denunciation of child labour, using his home town as an example, the book being sub-titled as exemplified by conditions in Lancashire.

He was a man of advanced ‘liberal’ views and became a close friend of the gay socialist Edward Carpenter, becoming his (unpaid) physician. The two, with Carpenter’s lover George Merrill, went on holiday together to Morocco.

He had a long marriage to Bertha and they shared several cycling holidays in Britain and abroad. They moved to Bispham in the early 1920s when he became ill.

He died in September 1927, outliving his good friend Wallace by a year, though his final years were blighted by poor health.

Johnston’s archive, including his diaries, are in the safe keeping of Bolton Library Local History Centre.

Details of Paul’s new book Moorlands, Memories and Reflections, featuring more on Johnston and his circle of friends, can be found at www.lancashireloominary.co.uk

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here