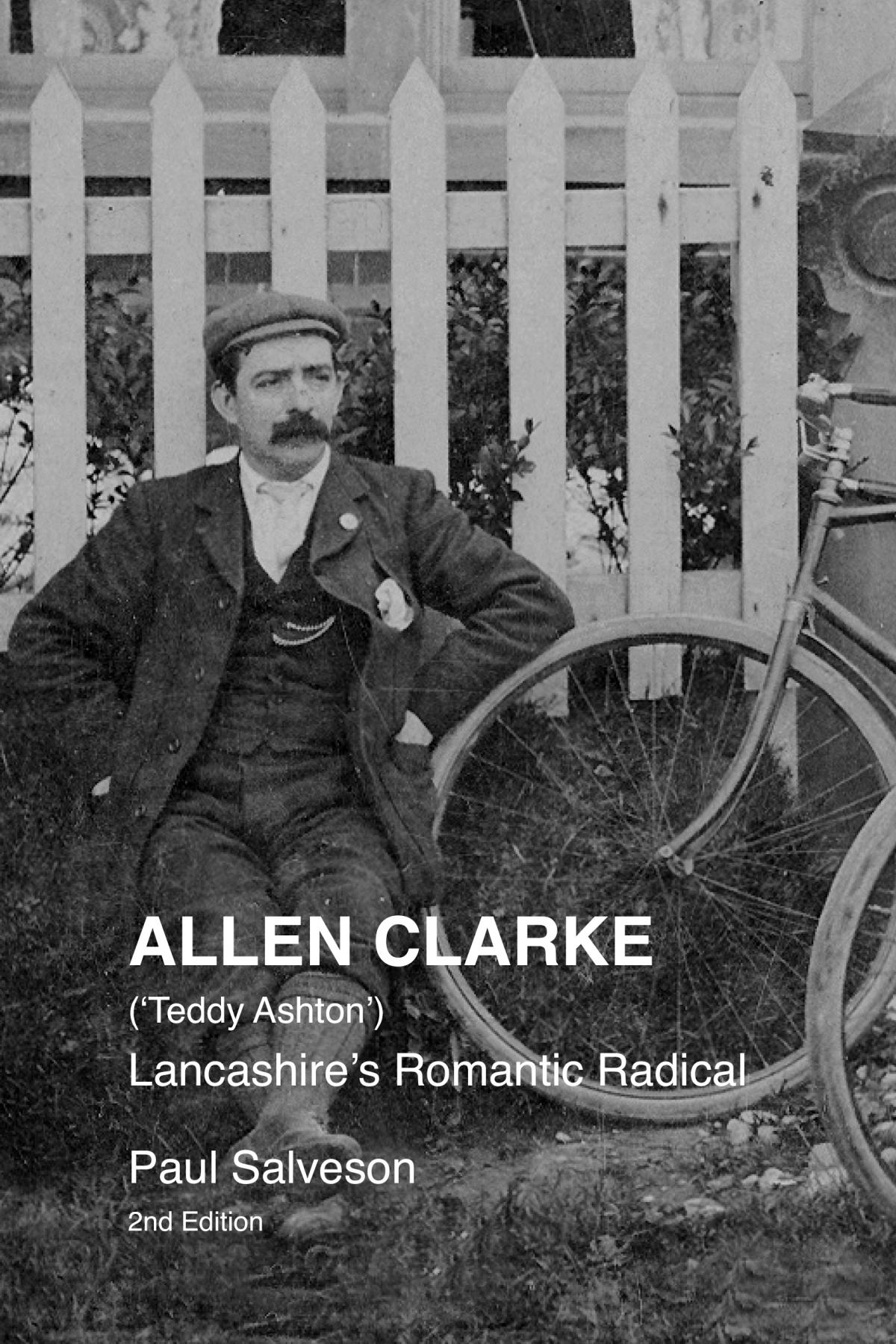

Professor Paul Salveson is a historian and writer and lives in Bolton. He is visiting professor in ‘Worktown Studies’ at the University of Bolton and author of several books on Lancashire history

Allen Clarke, born in Daubhill in 1863, was one of the most important figures in Northern literature between the early 1890s and late 1930s.

Today his work is largely forgotten. Yet he was loved by tens of thousands of Lancashire mill workers and had an astonishing output of dialect sketches, poetry, journalism and works of philosophy.

He wrote over 20 novels, most of which were never published in book form, but appeared in newspapers across Britain and even beyond.

Most of his novels are set in Bolton, where he was born and bred. He was never part of the upper class literati – his parents were mill workers, and he started his working life as a half-timer at the age of 11.

His subject matter was the people he knew and the places he grew up in. His parents encouraged his love of writing; at the age of 14 he won a national prize for one of his poems. As his writing developed he had a clear aim – to be a writer of the people and for the people.

In 1896 he said: “My aim today is to give the working class life (of Lancashire principally, for that I know best) faithful expression in the literature of England.”

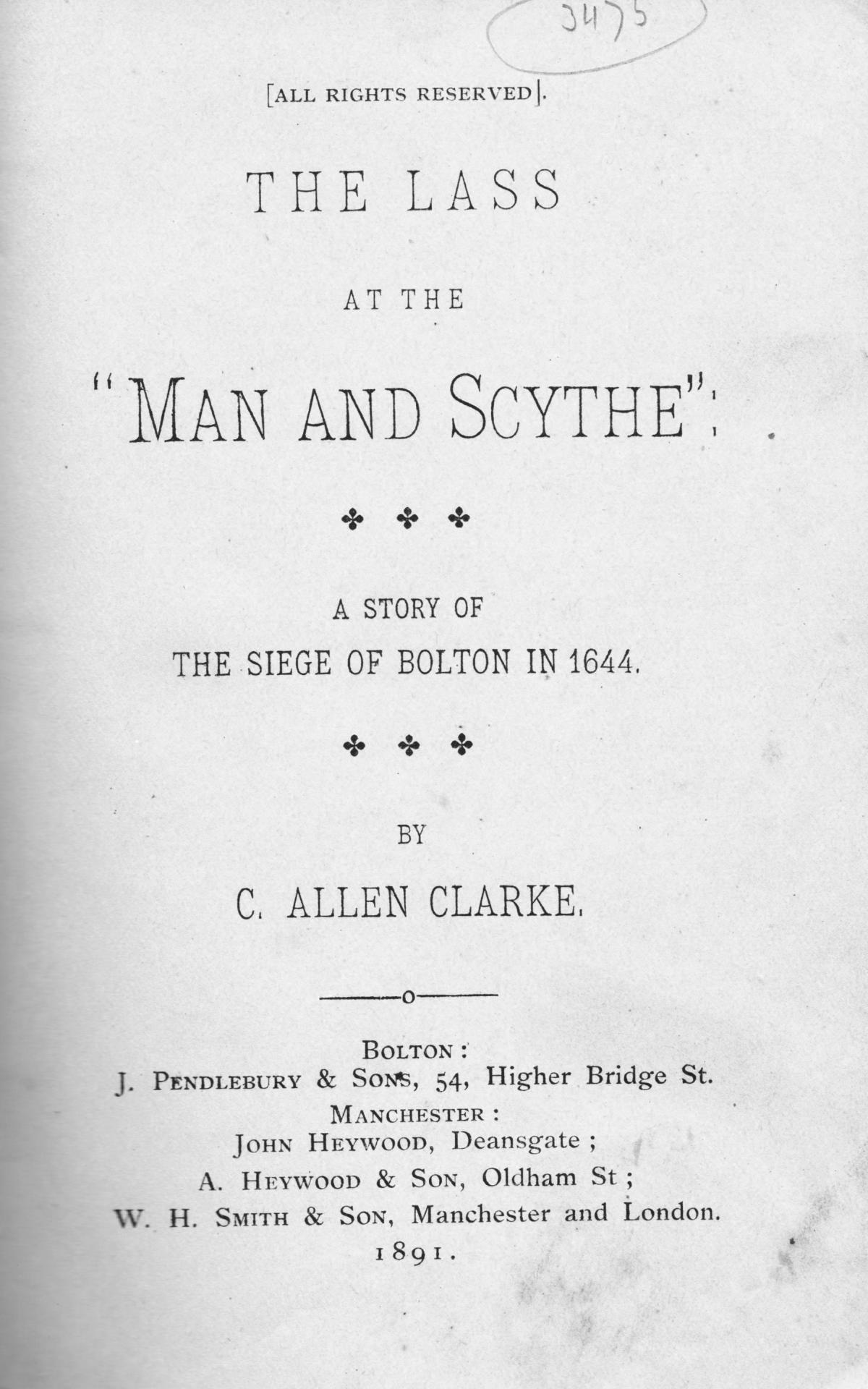

His first published novel was The Lass at the Man and Scythe, written in 1889 and published in book form (by himself) in 1891. It was printed by Pendlebury’s of Bolton. The ‘Lass’ was later revised and extended, re- titled John O’God’s Sending.

It is a story of the Civil War, set in Bolton in 1644. It contained many of the themes that featured in his later novels. There is tragedy, a conventional love story, and a healthy dose of radical politics. His preface to the first edition of the book is an early example of his attempt to engage the reader: “With the aid of that wizard’s wand, a pen, dipped into that magic fluid, ink, the Boltonians who live and move again (at least I hope so) in the following pages have been temporarily raised from the dead. For taking the liberty of resurrecting them somewhat prematurely I beg their pardon. If I have done the business clumsily and inconvenienced these characters in any manner whatever I humbly tender my apologies. I am but a novice at the work……”

The novel revolves around the ancient Bolton pub, The Man and Scythe, still standing opposite the town cross, where the Earl of Derby was executed for his part in the Siege of Bolton in 1644.

Royalist soldiers, led by the Earl and Prince Rupert, besieged the town siege and massacred a large number of the townspeople, who supported the Parliamentary side. Clarke sets the wider political context in characteristic style.

He wrote: “The war that was taking up the time, money, and blood of the nation at this period was a struggle for supremacy between King and Parliament. The King wanted to do exactly as he pleased; the people, as represented by Parliament - wanted to do what they pleased.

“As a rule, when two parties each resolve to please themselves, it pleases neither. It was so in this instance. Both were obstinate. The monarch had on his side ‘the divine right of Kings’; but that is not much when opposed to the superior force of revolutionary masses.”

Clarke favoured the Parliamentary side but the novel shows that things are never black and white, and creates some positive, human characters amongst the Royalists.

A very important part of this first novel is the extensive use of dialect amongst its characters.

Early in the novel we find this exchange between Bolton characters, sat in the pub debating the war:

“How think ye the cavaliers will fare in York?” asked Isaiah Crompton.

“They sen they’ll howd eawt till th’King sends a force to their relief,” said Cockerel, “though for my part I think as they’ll have hard wark for’t keep Fairfax eawt o’th’city.”

“Wheer’s that wild Prince Rupert, what feights like Satan?” queried Roger Roscoe, a farmer.

“Deawn tort Lunnon, somewhere, i’them forrin parts,” replied another.

The novel was a success. Readers enjoyed the local connections, the ‘homely’ characterisation and use of dialect, the love interest combined with the horror and violence of the siege. It was subsequently re-written and enlarged as John O’God’s Sending and published in book form in 1919.

His next novel was The Knobstick, completed in 1891 and serialised in his paper The Bolton Trotter from October 21, 1892 ,and later published in book form.

Knobstick is an abusive Lancashire term for strike-breaker or ‘blackleg’ which has long gone out of use. This time Clarke used a near-contemporary event – the Bolton Engineers’ Strike of 1887 – as the backdrop to the story.

Some of Clarke’s themes from The Lass at the Man and Scythe re-emerge: a love story, a dramatic event – in this case the strike, with a powerful riot scene. The novel was celebrated by the East German writer Mary Ashraf in a scholarly article in 1976, who identifies the beginning of the novel as being of very high literary quality, suggesting “if that quality had been maintained throughout, the book might have been a masterpiece”.

The engineers’ strike is a central part of the novel and Clarke builds up a sense of an impending struggle through the union secretary Peter Banks and his wife:

“We’re gooin to strike Jane,” said Peter Banks to his wife one evening, speaking, as he always did to her, in the dialect.

“God forbid!” she exclaimed.

“Well, it’s so for aw that,” continued Peter, “an I’m afraid as it’ll come off this time. Th’men’s gradely dissatisfied, an fully resolved to have mooar money…It’ll be a mighty struggle if it begins and there’s dozen’s what’ll ne’er see o’er it. Of course eaur society’s very rich at present an’ con howd eaut a good while; but t’mesturs con howd eaut longer. I’m willin for t’ strike anyday, but I’d rayther not. I con feight as weel as anybody when I’m put to, but it seems a silly gam to me.”

It’s melodramatic stuff but well told; it appealed to the readers he was aiming at. After tragedy there is a happy ending with hero and heroine married; the strike ends and a new era begins in the town, with working men elected to the council.

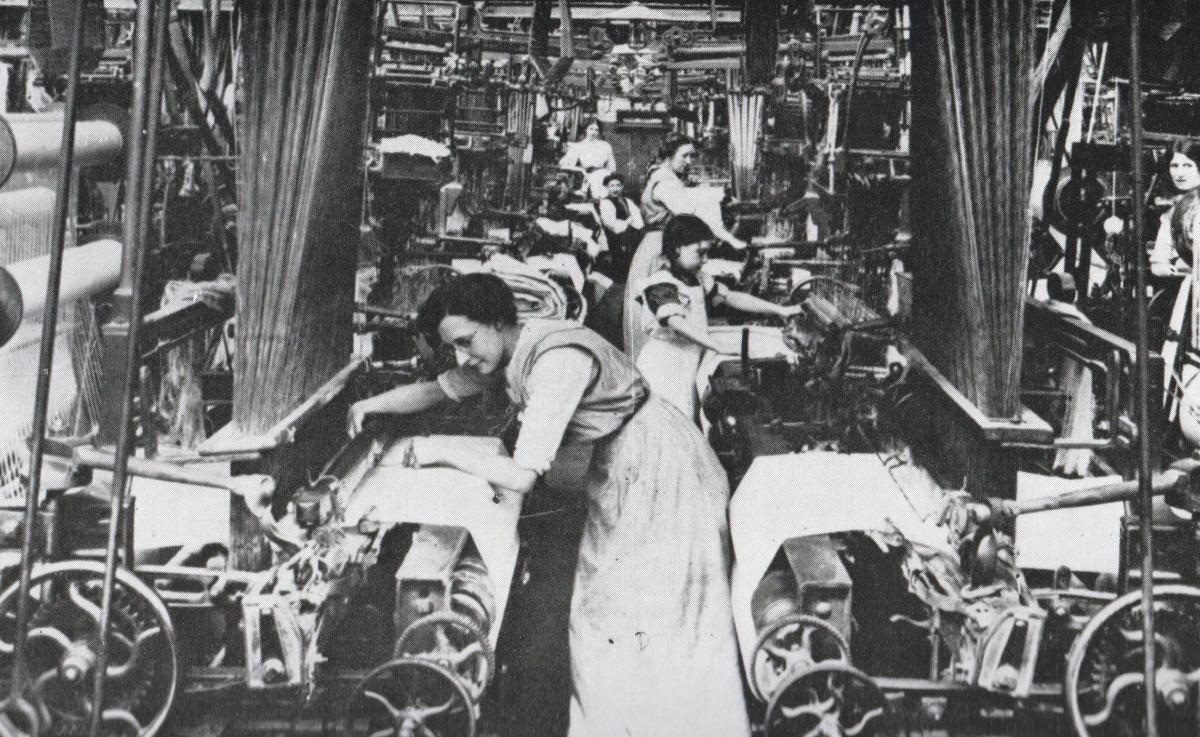

During the 1890s Clarke was working flat out, editing and publishing his Northern Weekly. He wrote much of the copy, including a steady stream of novels including The Little Weaver, Lancashire Lasses and Lads, A Daughter of the Factory, A Curate of Christ’s, For a Man’s Sake and Slaves of Shuttle and Spindle. All of these are set in the Lancashire mill towns, mostly Bolton - often fictionalised as ‘Spindleton’.

The Little Weaver proved popular with his readers, who identified with the characters in the tale; as so with most of his novels, it was about people like them. It has this powerful image of a mill coming to life on Monday morning:

“Then, slowly, at six o’clock precisely, there stole a huzzing murmur on the silence; the shafts began to revolve, the straps that chained the looms creaked, stretched and yawned, as if reluctant to begin their duty, and commenced to climb languidly up to the ceiling, quickening their speed with every turn; the huzzing murmur grew and grew; the weavers touched the levers of their looms one by one, and set them on. The murmur had now become a rattling roar; the sound swelled; the straps whizzed faster; the threads of the warp flowed into the loom like a slow broad stream, and the shuttle darted across them like a swallow, binding them together and making them into cloth; there was creaking and groaning of wheels; the hissing and spluttering of leather straps, as if the animal moaned painfully in its hide; the air grew warmer; the noise became deafening; you could not hear your own voice; and the weaving shed was in full swing.”

Clarke hated what industrialism had done to the Lancashire countryside. In Driving - a tale of weavers and their work, he contrasts what Lancashire once was with how it is today, but even here there is a sense of a tremendous human achievement which has somehow been abused:

“What a marvellous transformation James Watt’s steam engine, aided by the spinning and weaving inventions of Kay, Hargreaves and Crompton had wrought in a hundred years; an agricultural and pasturing shire had been turned into a county of manufacture; Lancashire’s wild moorland vales had become the smoky workshop of the world; and once sweet hillsides were now cinder-heaps and once- bright brooks were now sinking sewers.”

Lancashire Lasses and Lads, set in Bolton and Farnworth, was first published 1896 and in book form 10 years later. The hero, Dick Dickinson, is the son of a factory master who forces his son to leave the family home and ‘descend’ into the working class, where he meets and falls in love with a young weaver, Hannah. Again, Clarke is fascinated by the awesome power and beauty of the factory contrasted with the reality of life inside the mills. Dick Dickinson, when he arrives in Bolton early in the morning, sees the mills coming to life:

“Lights began to show in the great factories of four or five stories, with their many windows. Soon they were all lit up like a vast illumination. ‘Very pretty to look at from the outside, and at a distance on a black frosty morning,’ said Dick, ‘but it’s a different matter toiling inside them’.”

Clarke was a friend of the Tillotson family publishers of The Bolton Evening News and Bolton Journal, both of which carried his writing, long after he had left Bolton to live in Blackpool. The company set up the Tillotson Newspaper Fiction Bureau to syndicate novels and short stories for newspapers across the British Empire.

Many of Clarke’s novels and short stories were published in such seemingly unlikely newspapers as The Forfar Herald, Western Evening Herald, The Devon Valley Tribune (Clackmannanshire) and The Kilrush Herald and the Kilkee Gazette of West Clare. Quite what they made of the Lancashire dialect I can’t imagine.

Clarke’s novels were of their time but remain readable and offer real insight into Lancashire life in the late 19th century. Some of them deserve re-printing, perhaps starting with ‘The Knobstick’.

The new edition of Paul Salveson’s Allen Clarke (‘Teddy Ashton’) - Lancashire’s Romantic Radical will be available from September 1 price £18.99. See www.lancashire.loominary.co.uk for pre-publication offer of £15 with local delivery. Email Paul at info@lancashireloominary.co.uk for details. Moorlands, Memories and Reflections, a centenary celebration of Clarke’s Moorlands and Memories, is available at £20

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel