Professor Paul Salveson is a historian and writer and lives in Bolton. He is visiting professor in Worktown Studies at the University of Bolton and author of several books on Lancashire history

Bolton is a multi-cultural town and has been for centuries, going back to the Flemish weavers who arrived in the 1300s. By far the largest wave of immigration in the 19th century came from Ireland and this was explored in a previous Looking Back feature.

Those first Irish immigrants were fleeing dire poverty and starvation. They settled in Bolton and created their own institutions – cultural, religious, educational and political. By the middle of the 20th century they were very much integrated into Bolton life, but have kept their distinctive cultural identity.

By the early 20th century Bolton’s Irish community was well established, though largely still confined to specific parts of the town – ‘ghettos’ as some Irish people themselves described them. The area around St George’s Road and School Hill had a large Irish community, often living in poor housing conditions. Parts of Halliwell had large concentrations of Irish families, as well as Daubhill.

The link between Roman Catholicism and Irish people was extremely strong. The most visible expression of Catholic identity was the annual Trinity Sunday walk which began as early as the 1840s. By the beginning of the 20th century, the walk had become a huge event with tens of thousands of children and adults marching through the town after assembling at Moor Lane. Most churches and schools would be led off by local brass bands. The highlight of the procession was the ‘march past’ overseen by the Bishop of Salford from an upstairs room in The Swan Hotel.

The beginnings of the century saw the rise of nationalism in Ireland culminating in the 1916 Easter Rising in Dublin and the War of Independence which followed. The Irish Free State was formed in 1922, comprising 26 of the 32 counties of Ireland. However, links between the two countries remained strong and generally cordial. During the Second World War many Irish nationals signed up to join the British armed forces to fight Hitler.

Irish culture was encouraged in many Bolton schools, notably St Joseph’s in Halliwell and St Gregory’s in Farnworth. A branch of the Gaelic League existed in Bolton for a while. Bolton’s first Irish ‘cultural festival’ was held in 1909 featuring music and dance. It ran each year until March 15, 1916, held within days of the Easter Rising. No further Irish festivals took place in Bolton until the 1980s.

A branch of the Irish Labour Party was formed in Bolton in 1919 but seems to have been short-lived with most members joining branches of the local Labour Party and becoming involved in the life of the town generally.

George O’Neill was the first Irishman elected to Bolton Council, serving from 1920 to 1929. Many more were to follow. Gradually, Irish people were ‘coming out of the ghetto’ and playing important roles in the civic and economic life of the town.

Bolton’s Irish community produced some highly talented people who became nationally famous. Perhaps nobody did more to ‘put Bolton on the map’ than Bill Naughton, from a humble Bolton Irish family in Daubhill. He was born in Ballyhaunis, Co. Mayo, in 1910 and came to Bolton at the age of four. He was educated at SS. Peter and Paul’s and then got work in the local mills, then worked as a coal-man and later became a lorry driver.

In the mid-30s he volunteered to be an ‘observer’ for the famous Mass Observation study of Bolton (‘Worktown’) which documented the lives, habits and attitudes of thousands of Bolton people. The writing which made his fame came after his move to London in 1938. Some of his books, many inspired by his early life in Bolton, were made into popular films such as Alfie and The Family Way. His life and work is celebrated and promoted by the Live from Worktown group (www.livefromworktown.org).

The flow of migration from Ireland to Britain continued through much of the 20th century, typically in response to economic conditions at home. The Irish economy was sluggish during much of the inter-war period and despite the emergence of the Irish Free State, many young Irish men and women made the reluctant decision to leave. The classic pattern of emigration emerged, which has been followed by subsequent waves of migration from South Asia to Bolton.

Irish migrants would go to places where they had family, or where they, or friends and family, knew somebody. Clusters from particular towns and villages developed, often united in ‘county associations’, eg The Roscommon Association.

Thornleigh College was established in 1925 by the Salesians of Don Bosco, at Sharples Park in Astley Bridge, to provided a means for Catholic boys to get rigorous education. Mount St Joseph’s, Deane, was established as early as 1902 by the Sisters of the Cross and Passion as a girls-only college. Between them, they provided the human resources for an emerging Bolton Catholic middle class. Most of their protégés were from Irish family backgrounds, as indeed were many of the teachers.

Bolton’s Catholic schools encouraged the celebration of Ireland’s patron saint, St Patrick. Well into the 1960s, on March 17 children, myself included, would proudly sport fresh shamrock on their lapels.

Personal stories can often reveal a bigger picture. Gerry Connaughton came to Bolton from Castlerea in Co Roscommon in 1956 at the age of 19 when the Irish economy was in severe difficulties. Many of his neighbours had emigrated to Australia, Canada and the USA but he chose England “because it was near and I knew people there.”

He got work in Birmingham but was made redundant. He went home but things were no better so packed his bags once more and settled in Bolton, where he knew some friends from Castlerea. He lived at a house on St George’s Road and was soon joined by the rest of his family – mum and dad, five brothers and two sisters. His first job was on the railways, based at Trinity Street station but covering vacancies at smaller stations like Farnworth and Bolton.

Like other large employers the railways were desperately short of labour, in part because of a flu epidemic at the time. “I came down for an interview and the inspector asked, ‘could you start now’?’. So I did.” His railway career was short-lived but it gave him a start. Gerry worked away from home in the construction industry before settling down to run his own construction business – Cotscovian Ltd – which supplied local firms such as Cormar Carpets.

He enjoyed life in Bolton. “There was a dance at Jim Logan’s Dance Hall on Sunday nights where many Irish lads and girls met,” he said. “There was a strict ‘no alcohol’ rule, you could only get orange juice!”

The Irish Catholic community’s spiritual needs were well catered for and Gerry attended either St Patrick’s or St Edmund’s, both in the town centre.

Gerry looks back on Bolton in the late 50s with mixed feelings. “There was some hostility and prejudice towards Irish people,” he recalls. “We were the Asians of the day, living in poor housing and usually doing temporary jobs or work that nobody else wanted.

“Then we went up the social ladder, some of us getting professional jobs and moving to the likes of Harwood or Bromley Cross. Bolton’s Asians have followed us, with new generations of immigrants coming from other parts of the world.

“I love Bolton – like many others, I came here with nothing and Bolton is now very much home but I’m able to return back to Ireland when I please!” Gerry sent his children to Mount St Joseph’s and Thornleigh. He now lives in Harwood.

The 1970s and 1980s was a difficult time for the Irish in England with ‘The Troubles’ raging in Northern Ireland. In some ways it encouraged a stronger sense of ‘Irishness’ amongst the expatriate community, with many adopting Irish spellings of their names. A branch of the Irish in Britain Representation Group was established and Bolton’s Irish Festival, last staged in 1916, was revived in 1982. Irish music became popular, with bands like The Wolfe Tones and Dubliners attracting huge audiences. When the Northern Irish MP Bernadette Devlin spoke at Bolton’s Albert Hall in 1972 she was welcomed by a huge audience.

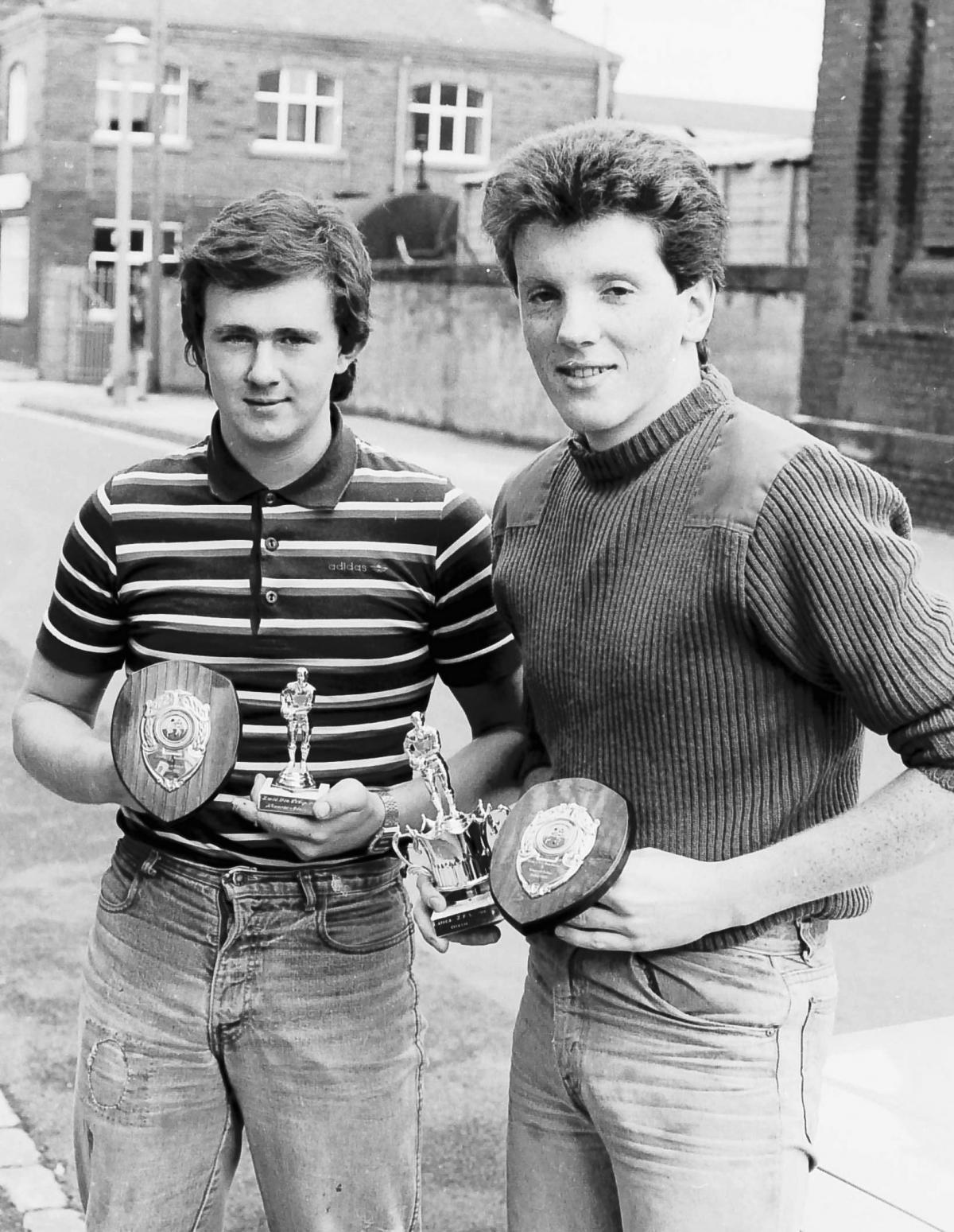

Gaelic football, organised through the Gaelic Athletic Association, was popular in Bolton. Shannon Rangers encouraged young Irishmen to play ‘the national game’. In the late 1980s a ladies section was formed and became part of the Lancashire GAA ladies league. Irish dance remains popular in Bolton, though Covid-19 has limited performances. The Shamrock School of Irish Dance, based at Brazley Community Centre, Horwich, delivers traditional Irish Dance classes to children and young people from the age of two to 18. Teacher Alexandra Cummins said “We have many families wishing to continue their Irish heritage and culture through their children learning to Irish Dance.” (www.facebook.com/theshamrockdancers)

The Bolton Irish Centre was established in 1999 at 25 Lever Street. Over the years it has hosted ceilidh dances, concerts and plays as well as a range of social functions. It been forced to close due to Covid-19 but is hoping to re-open when restrictions are lifted.

One of its committee members is Liam Hanley who said: “The centre is a place where anyone with a love of Irish music, sport, history and culture is always welcome. The club also hosts pool, darts and dominoes matches, so – when we’re open again - come down to Lever Street and give it a try.”

Bolton’s Irish community is well established and in recent years many sons and daughters have played important roles both locally and nationally. The late Councillor Guy Harkin, from a Bolton Irish working class family, went to Oxford and had a distinguished career in local politics. Danny Boyle, Peter Kay and Paddy McGuinness each have Irish connections.

For details of Paul’s new book Moorlands, Memories and Reflections, featuring aspects of Irish history in Lancashire, visit www.lancashireloominary.co.uk

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel